Jan 8/2022 by B Nimri Aziz

There are perhaps five million Arabs who identify as Americans, our earliest ancestors having arrived here almost two centuries ago. Many more Arab migrants reside in Canada, throughout South America and across the Caribbean Islands.

Etel Adnan, whose work is being celebrated in an exhibition at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, was Arab American. Although she lived in Paris for the past three decades, before that Adnan lived in Sausalito, California. I am an Arab American; so are Ralph Nader, Leila Ahmed, Rashida Tlaib and Naomi Shihab Nye. You’ll find us engaged in all fields—education, industry, medicine, journalism, community service, sports, politics and the arts– and practicing many faiths.

I offer this as context for the splendid exhibition featuring Etel Adnan at New York City’s prestigious showplace, The Guggenheim. Although contrary to what some claim, recognition of her talent did not arrive late in Adnan’s life. For years, her work has been widely exhibited and celebrated in Europe. Moreover, while she surpassed any specific religious identity, Adnan was an unequivocally proud Arab woman.

The Guggenheim show, now in its final days, respectfully presents Adnan’s paintings and drawings. What’s I find reproachful is its program concerning her poetry. Given the reach of this important forum, the museum’s plan for a public reading of Adnan’s poems is flawed.

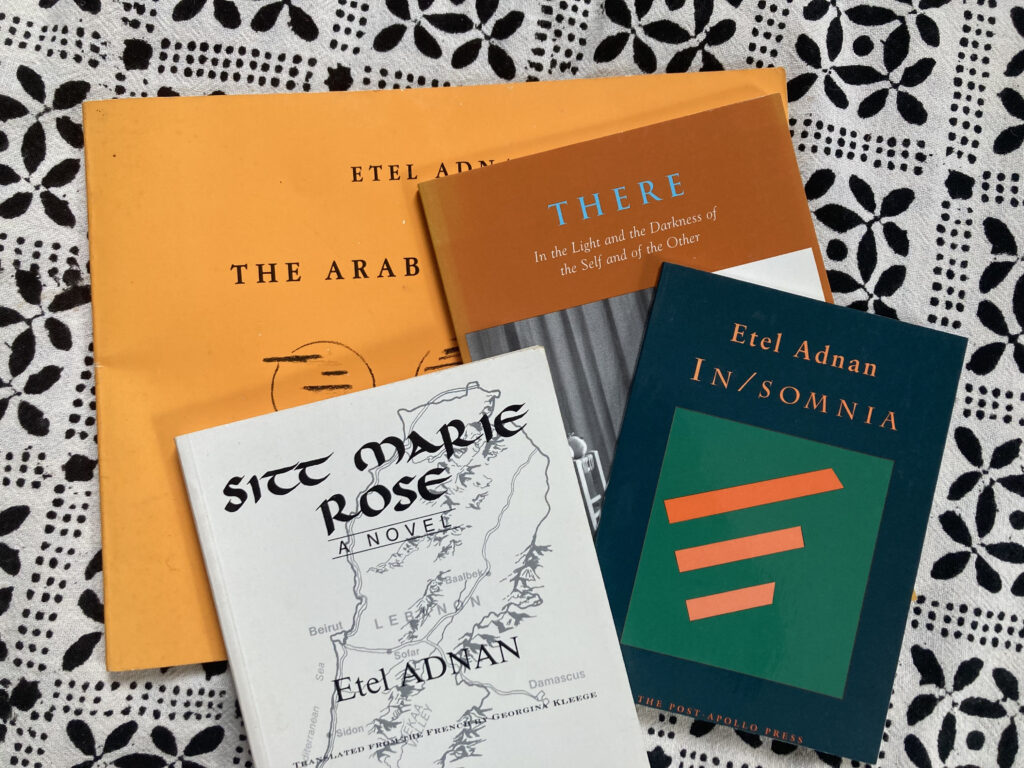

Etel’s first poetry collection appeared in 1966 (Moonshot, Beirut). Starting with her novel Sitt Marie-Rose she published in collaboration with Simone Fattal, founder and director of Post-Apollo Press. Best known for poetry, Adnan also penned plays and essays, some in French and Arabic as well as in English.

Initially, I was delighted to learn that readings of Adnan’s poetry were planned for January 10th, the final day of the NYC exhibition. This would introduce Americans to her important written work. (Although referenced in the captions accompanying Adnan’s paintings, I could find none of her books available at the Guggenheim bookstore.)

Etel’s writing is for the most part not culturally specific. This is understandable for someone with her breadth of experience and talent. Remember, she was a professor of philosophy for some years.

Her universalism is apparent in both her art and her writing. However, as anyone who knows her is aware, her Arab roots lie not far from the surface of her work. Those who worked with Adnan know how firmly she identified as an Arab America. She presided over the founding of the Radius of Arab American Writers (during my tenure as director) from 1992 to 2005, drawing in established figures while also attracting emerging writers.

This brings me back to the Guggenheim’s deficient plan for the forthcoming literary program in honor of Adnan.

If Arabs in America have any public literary profile, it’s as poets. Our best known, from Khalil Gibran to Naomi Shihab Nye to Mohja Kahf and Khaled Mattawa, have established a tradition that today includes hundreds of fine authors actively publishing in the U.S. Yet, the Guggenheim’s program– probably the most far-reaching presentation of Adnan’s work seen and heard in this country– includes not a single Arab American in the list of five participating readers. How is this possible?

Arab institutions in the U.S. include at least two literary organizations (RAWI and MIZNA) and the Arab American Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. In 2000 Lisa Majaj and Amal Amireh edited a collection of essays on Adnan’s work and life. In her honor the University of Arkansas Press publishes a series on Arab American poetry (edited by two of our leading poets). English departments across the U.S. include courses on our literature.

Can you imagine that any celebration of African American literature would exclude African American readers today? This challenge applies to Asian American literature, Latinx literature, Native American, Canadian, French, or Australian literature, etc.

Who decided on the presenters at the forthcoming Guggenheim reading? Did some indolent staff member simply call a local university or google Poet’s House to hastily assemble a few names.

Colonial mentality still rules, even with exhaustive search tools, even with Arab American literature now well established. Perhaps our Arab community outreach is still weak. Nevertheless, along with America’s enduring colonialist value system, academic nepotism is likely an additional factor in the program’s omissions. The Guggenheim Museum must be called out for its laxity. It has missed the opportunity to design a truly respectful literary program for one of our most esteemed and loved heroes.