This is a story of two revolutionary women Yogmāyā (1860-1941) and Durga Devi (1918-1973), both early 20th C. reformers from East Nepal, who challenged corruption and dictatorship,. Those histories were deliberately suppressed and nearly forgotten, but revived through persistent work by BNAziz who followed faint, hardly verifiable traces.

Aziz presented her early accounts of the women at international seminars in 1990 and 1991, later published in volumes of collected conference papers. Then in 2001 she developed the biographies of Yogmaya and Durga Devi into this volume, Heir to a Silent Song, along with three short portraits of rural life in the 1970s and 80s, and her account of arriving at the holy site where she launched her research in 1980. The Nepali language text sarvatha yogbani, utterances of Yogmaya, are in the appendix. (See excerpts and reviews below). After 20 years of transformations in Nepal led to more freedom of speech and openness about its political history, the early campaign of Yogmaya- the more radical of the two women- entered the national discourse. Also see the author’s 2020 book with her review of the last quarter century that ended an era of censorship, and her assessment of these rebel women’s place in Nepali history. (see more photos under Arun River Valley)

Excerpts

“Yogmaya had a two-pronged agenda, not just one,” explained ManaMaya.” Her first target was the cultural and religious oppression of the time. Her second object was our ruler, the Prime Minister, who along with his generals allowed corruption and inequality to prevail. Our master, Shakti Yogmaya, showed us how these two evils are intertwined, and she feared neither.”

Yogmaya launched a brilliant and a daring political campaign from her base in the hills of East Nepal. It took place during the 1930s, and ended in 1940 with her death, along with sixty-eight of her followers who one by one followed her into the thundering current of the Arun River. After leading a campaign for reform and justice. Yogmaya finally confronted the ruler with an ultimatum: “If you do not grant us justice, we will die,” she declared. Juddha Shamsher responded by sending his army to round up the protesters.

The tragedy that resulted remains a stain on the government. The Nepalese authorities covered up the episode and banned all mention of her. Her campaign was thoroughly expunged from the nation’s historical record and almost lost in its national consciousness. But the power of the verses composed by Yogmaya, the hajurbani, survived. And there lies the story.

I am the child in your lap.

You are the babe in mine;

There is noting between us, nothing at all.

Your eyes have tears, just like my own.

On the surface these lines may appear to be politically innocent, they are not. They embody the very principle of equality. They call for purity and mutual respect. They are tender reminders of the sensitivity of all of our common needs, joys and sufferings.

Manmaya uttered another of Yogmaya’s verses filled with praise of nature and also love of land or homeland.

Supreme among peaks, this our Himalayas

From where waters flow, Arun merges

And with Barun flows on

To mingle with Irkhuwa.

These line hints her political goal to move towards equality. Her effort to challenge the system is opposed by priests, the public, and the government. But still Yogmaya attacks.

Virtue, stained by greed.

Justice undone by bribes.

Though innocent, we lost

Thus we’re twice punished.

Eventually, Yogmaya’s teachings became a comprehensive utopian ideal, linked with a non-violent political strategy she devised to bring it about. It began four decades before the United Nations sponsored an international convention on women, before the current generation of American feminist was born, and even before Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent ‘Quit India’ movement (a campaign to rid India of British occupation) was underway. But Yogmaya’s movement went further because it included a call to end injustice against women and girls.

The text is preceded by two quotations by Rudyard Kipling and Martin Luther King. They are “If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten; and “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

[Excerpt from “Shakti Yogmaya”, which was edited and published in Heir to a Silent Song, 2001, accompanied by other material stemming from Aziz’s 1980s research in Manakamana, Sankhuwasabha.]

“In East Nepal, early in this century, an extraordinary uprising took place. Led by a woman of exceptional ability, it directly challenged the Rana regime and the Brahmanically-determined power structure prevailing in Nepal. Yet that uprising and the personage of its leader are almost totally obliterated from the historical memory of the Nepali nation. In this article I try to throw light on that obscured history. At the same time I reflect on some of the challenges we face as scientists as scientists exploring the role of women and peasant people in our lives and our work.

As many people familiar with my research will know, a decade ago I became interested in the experience of pilgrimage in South Asia. I made several journeys to specific Himalayan sacred places and wrote about them (Aziz 1982; 1983; 1987). My curiosity about pilgrimage originated when, sometime earlier in Nepal, I witnessed Tibetans’ relationship to the relics of Langkor; pilgrims drew personal power from a history told in an account of a set of stone relics carried to safety from Tibet to Nepal in 1959 (reported in Aziz 1979, “Indian Philosopher as Tibetan Folk Hero”).

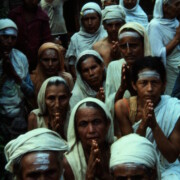

Before that of course like anyone who travels in India or Nepal, I was familiar with the sight of women and men en route to a monastery, an alpine lake, an enchanted cave, a riverbank, or the residence of a holy person—to encounter the divine.

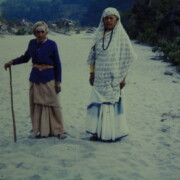

In 1980 when I began to think about this experience more systematically it was also a time when I began to reflect on the limits of my past approach. It was essential to articulate my own voice within the anthropological texts I was interpreting, Ethnography, I decided, could not exclude self-reflection.

By that time, I had also simultaneously been convinced by the revelations from our feminist scholars of the 1970s, of the misogynist character of modern social science and history. In media and political life, in academic research and in language, in virtually every interpretive field, not to mention daily interactions, there was indeed a powerful selective exclusion or obfuscation or devaluation of the experience of women. Without really needing more evidence than studies available by 1980, I understood what the new feminist scholars were claiming. It left an indelible mark on me and I could never again view human relationships within the same narrow limits….

Reviews

Review by Dr. Dipesh Neupane, Dept. English, Tribhuvan University, Nepal

“Woods are lovely, dark and deep.

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

And miles to go before I sleep.” (Robert Frost)

The above quatrain from Robert Frost strikes me a lot when my mind bends upon the unwavering contribution rendered by a towering academic giant and vibrant researcher Dr. Barbara Nimri Aziz to the historical, the cultural and the anthropological domain of Nepal. Her persistent, consistent and untiring dedication to research and critical writings connotatively imply the essence of Frost’s poem mentioned above. As a prolific and versatile writer, critic, anthropologist and a researcher, Dr. Barbara Nimri Aziz strives to unravel the hidden and the suppressed history of the different countries of the world. As a Nepali researcher, I would like to recapitulate her contribution in relation to the Nepalese history and culture in this brief critical review of her renowned book “Heir to a Silent Song” : Two Female Rebels in Nepal”, one of the resourceful books among many other books she produced till date.

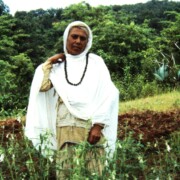

It won’t be an exaggeration if I state that she has produced innumerable critical and research writings on varying burning issues across the globe, beside writing resourceful books. It is a matter of immense shame for Nepalese writers and researchers who ignore the minor historical events and cultural facts of their motherland whereas a foreigner from abroad comes to Nepal and knock their doors , and even open their eyes for disclosing and uplifting the unwritten and the ignored history of Nepal. It is none other than Dr. Barbara Nimri Aziz who came to Nepal from America in the year 1981 , and happened to visit the eastern hills of Sankhuwasabha and Bhojpur districts in course of her research journey. When she reached Manakamana, a very quiet place near Tumlingtar of Sankhuwasabha, she happened to hear the alluring lyrical verses recited by a Bhaktini( may be Manamaya by her name) . The moment she came to know that those verses belonged to another Bhaktini- Yogmaya , Aziz , being impressed with the rhythm and rhyme of the verses , decided to learn more about Yogmaya and her lyrical verses which she often calls Hajurbani , publicly known as Sarvartha Yogavani.

Afterwards, with her keen interest, she came to contact with a handful of Nepali people and began to collect the facts and stories about Yogmaya – the first female revolutionary, poet and social reformer of Nepal, with utmost dedication . After a long time study and field visit, she was able to recapitulate Yogmaya in her renowned prose work- “ Heir to a Silent Song”, depicting her social, political, religious and economic movements in the Nepalese society on the one hand , and her teachings and preaching lying inherent in her lyrical verses on the other. The moment Yogmaya was languishing in the blurred history of Nepal , Aziz’s book became a milestone for the iconization of Yogmaya in the main stream of Nepalese history. Aziz portrays her as a poet, teacher and insurgent in her book. She seems to be more concerned with Yogmaya’s teaching and preaching underlying in her verses, and her rebellious movements against social anomalies and aberrations, rather than her personal biography, which does not count much for research study. Hence, I commend her work wholeheartedly and extend my hearty indebtedness and reverence towards her contribution she made in the research field. I enjoy being her descendant in this field. In the absence of her work, I would have been crippled in want of references and ideas for my research study. It is my pleasure to honour her as the first foreign researcher on Yogmaya.

“Heir to a Silent Song” is a prose work that she produces after her long time study and field research . Beside the delineation of her travel account and the rustic life of people living in the eastern hills, the prose echoes the subaltern voices raised and represented by Yogmaya and Durga Devi as a protest against evils existing in the social system . As an epitome of the voices of the voiceless, it depicts the plight, the grievances and the pathos of basically these two female rebels from the eastern hills of Nepal.

Subaltern studies are the study of social protest, and the social exclusion and exploitation. Since subaltern refers to the group of oppressed, suppressed and marginalized people, Aziz ventures to portray them as the messiahs of subaltern people in her work. This book strives to delineate them as the representative figures of subaltern aesthetics. It attempts to answer the questions: “How do Yogmaya and Durga Devi represent subaltern voices? and what do they combat for ? ”. Aziz presents how two women combat for female rights and justice for the poor and low class people in the contemporary society during Rana regime. The desperate struggle of two subaltern females against social evils like caste and gender discriminations, corruption, exploitation, fraudulent activities etc. is a striking thrust of the prose work.

In the inception of the prose work, Aziz describes her journey to the eastern hills of Sankhuwasabha and Bhojpur districts of Nepal, where she happens to hear about Yogmaya and Durgadevi as the dissidents of the contemporary social systems. Aziz discusses about how Yogmaya fights against Rana regime and so called high class Brahmins for the justice, good governance and equality, and how she attempts to weed out social evils persistent in the contemporary society, “Yogmaya employed religious ideals in a non-violent challenge to Nepal’s Brahmanic patriarchy and the elitist structure the high caste Hindus established across Nepal. She advocated social reforms for equality for equality (xxvi)”. The voices Yogmaya raises represent the voices of the marginalized, oppressed people i.e. subaltern group. Aziz remarks: “Her words are a tender reminder of the sensitivity of all of us. We have common needs, joys and suffering”, she said. Perhaps the tears Yogmaya speaks of here are the laments of men and women, bound against their will by society’s caste rules. Those laws destined some to be lower, and poorer, and to thereby suffer many deprivations. (36) . Aziz’s another focusing aspect of this book is about moral lessons, superb knowledge and wisdom lying inherent in Yogmaya’s lyrical verses. She , with a help of a Nepali fellow, has even translated Yogmaya’s Nepali verses into English so that non-Nepali speakers will also enjoy reading them.

The second woman she talks about in her prose work is Durga Devi from Falikot village , Sadananda municipality, Bhojpur . Aziz also depicts her as a messiah of the voiceless and the oppressed folks living in her society. Aziz remarks: “She pursued court cases, and waged a campaign against corrupt and indolent bureaucrats in local districts. Petitioners regularly trudged to Durga’s house seeking help, but she had no community of followers” (xxvi). Durga basically raises her voices concerning land inheritance, abuse of power, laziness of officials, rape and abuse, debt trickery and extortion . Her voices also represent the grievances of low class marginalized people. Aziz remarks: Durga’s goal was that government officials observe the law, that police apply the law, and that courts be fair. She appealed to the courts to keep her share of land after her husband died; she helped people who were cheated to name the culprits and demand justice from the police; she came to the defense of a violated child; she helped women who were abused; she badgered government clerk until they did their job. (88)

Though Durga was a child widow, and childless, she had a property rights from her husband’s family. Since women cannot challenge their husband or husband’s family for property, they often remain silent. But Durga is different from others as she daringly fights for her property right against her- in- laws after her husband’s demise. She struggles for eight years filing a series of cases in the court for the possession of her land. She continues her battle until he gets her victory. Though the police, clerks and merchants disdain the confrontational style of Durga, she never surrenders before them. Since Durga’s actions are against the existing culture of the contemporary society, they even misplace her files and even harass her at every turn. She continues her battle for her right as mentioned in the Muluki Yen. She launches her crusade for her rights representing the silent voices of the subaltern group.

Aziz’s prose work becomes a kind of historical record of the subaltern group represented by Yogmaya and Durgadevi. Their persistent struggle against higher class agents and government officials for the sake of human rights and justice are vividly and graphically depicted in her work. The next graphic portrayal of other females- the life of little Weaver girl and a girl child named Laxmi is also of paramount importance in her book. The predicament of such common people living in the rustic hills really captures everyone’s attention. The subaltern aesthetics inherent in her work is worth mentioning and worth researching all through time.

Some historical events and facts are intentionally suppressed by the so called autocratic rulers and higher class people since they may not favour their interest. Those events which match the favor of the ruling or elite class, they are highlighted and brought into the lime light. Those events which do not match their interest or favor will not be recognized, honored and even recorded in the historical domain. When the historical record falls upon the hands of lunatic rulers, there might be the question upon the originality of the events recorded in the history. Michael Foucault says, “ All the events of history are yet to be rewritten as it is power centered history of any time. ” The historical record of some minor events related to the lower or middle class people really becomes a vital source for learning and researching upon new issues. In this regard , Aziz lays a foundation stone in the research field by disclosing the languishing history of common folks.

The subaltern voices are the voices of the voiceless. Should subaltern voices get listened and recognized, there will be a true respect and honour to the norms and values of democracy. Otherwise, it will be the autocratic system of the government and social agents. In order to preserve the true spirit of democracy, subaltern voices like those of Yogmaya and Durga Devi should be materialized without much delay. The crusade of subaltern group for their rights and justice really shows the right path to the concerned.

Since Aziz’s book reflects the mission, vision, struggle and the social confrontations of both ladies, it has become a helping hand for many readers, historians and researchers like me for the further research activities. It has also rocked the conscience of the ruling class people and the government agents to respect the voices of the voiceless represented by both ladies.

Hence, Aziz’s Heir to a Silent Song has become a true source of historical and cultural study of Nepal. I wish her better research and writing career ahead ! My the almighty God rejuvenate her strength for her untiring job in the days to come !!!!

From ACROSS: A Bilingual Magazine with Informed Views, Oct 2001, Vol.5, No. 2. By Sangita. “Rebellion in Silence” (p 27) excerpt.

This book is written by a senior American anthropologist Barbara Nimri Aziz and is the result of her research of many years about who she describes as “two rebel women”. ….The book is remarkable for its quality of being the story of two obscure people who in one way or another did raise their voice against the oppression of the society that is male-dominated. The other quality about this book is the passionate involvement of Aziz in the historicity of the women of bhakti tradition, and at the same time with a Nepali woman writer of reputation, the late Parijat.

…But three cheers go to Aziz for doing this work. This is a result of her long years of love, concern and respect for Nepali women. I as a student of western literature and theories about women do make very humble confessions that Aziz spent more time, more years studying Nepali women than I have. My deep respect goes to her…

Related Articles

June 14/2025 by BNimri Aziz. If it would help awaken others to end atrocities and extinguish your own fear of being personally slandered, would you speak out like…

by BNimri Aziz June 14, 2025 Should I, or shouldn’t I? Can I, or can’t I? I may be alone. No villager who had accompanied me to protests…

by B Nimri Aziz. May 2025 Carried by Counterpunch “Starving children”, if you didn’t deduce the urgent it. (No illustrations necessary.) Starving Palestinians – of all ages. Not…

by B Nimri Aziz April 21, 2025. Carried by Counterpunch “Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk” is the title of a soon-to-be-released film featuring photojournalist Fatima…

by BNimri Aziz April 26, 2025 Moses Baptiste’s family laid their brother to rest on April 17th. But the Roscoe resident’s death leaves many unanswered questions Rockland town…

by BNimri Aziz March 22/2025 It was costly for British actor Vanessa Redgrave beginning in the 1970s, pilloried for her crime of speaking out on an unspeakable subject….