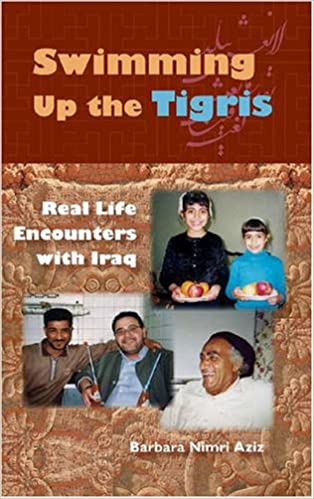

As Americans went about their daily lives through the 1990s, few imagined what Iraqi men and women faced under the brutal sanctions declared by the UN and strictly enforced by the United States. It lasted 13 years.

Barbara Nimri Aziz, a frequent visitor to Iraq through that period, saw first-hand what life was like for Iraqis completely cut off and shunned by the world.

Swimming up The Tigris reveals the power of Aziz’s combined skills in journalism and anthropology. Through her first-hand accounts, ordinary Iraqis speak directly to us. We learn of the breakdown of Iraq’s fine administrative and educational institutions, of needless deaths resulting from the embargo-ravaged once exemplary healthcare system, of the brain drain of its highly skilled professional class. We hear of deprivations, aerial bombardments, and local efforts to fight the wide-ranging embargo with no outside help whatsoever.

Drawing on intimate sources inside Iraq, the author reveals disparities between news reports of unfolding events and what Iraqi men and women were actually experiencing in the months preceding the U.S.-led invasion in 2003.

By revisiting this critical period, Aziz sheds light on illegal, cruel tactics used by the United States to destroy Iraq through sanctions well before the WMD ruse for all out occupation. This book offers an essential context for others to appreciate early opposition to U.S. policies, to understand embargo as the ‘real’ weapon of mass destruction, the rise of ISIS, and the disastrous American occupation of the nation.

Photos

Excerpts

Chapter 4: ” Mehdi—Iraqi Foreign Service Officer“

January 17, 1991, 7:00 pm, New York time: the American led assault began.

In their office Iraqi embassy at the U. N. Mission staff huddled together, smoking nervously, tapping their feet on the parquet floor, while they stared at the television, stunned and helpless as their nation was being bombarded. The most painful sigHt for Mehdi was the collapse of brides over this land’s great ricers. He stared at replays of the bombing of Jisr Muallaq…. Nasiriya Bridge was in tatters too. After a few days, his wife Suha was able to phone from Baghdad: “Keep the boys with you as long as you can”.

Mehdi’s boys survived the animosity of classmates and the setbacks to their household budget. Khalid, seventeen and Mahmoud, twelve, were sophisticated lads, modest and thoroughly trained in diplomatic protocol. They concentrated on their schoolwork and stayed close to home. “people will try to provide you. Be prepared. Be polite. Walk away. Keep your passport with you and don’t volunteer any information about yourself,” Mehdi cautioned them.

Even when Khalid was apprehended and held in the NY police jail for a night, his father was sympathetic. The problem had erupted on a quiet summer night when Khalid was having a soda with boys from his building at a nearby corner store….

Chapter 15: “HIM”

Iraq is not a large country. Yet within three generations it became highly modernized with a skilled, educated and forward thinking middle class. I met so many defined people in Iraq who cared about their country, who worked tirelessly to raise their children and to hold on to their dignity. Iraqis proved to be perceptive, ready and capable. They had much to contribute to the development of a strong civil society.

Seeing this professionalism and noting the basic goodness of the majority, one could not help asking: “Did no one listen? The reply was swift and unequivocal. “No did didn’t listen; he just did not listen to anyone.”

How could that be? He held council; he invited delegations; he made himself accessible to a wide representation of citizens; he took pride in reaching out to the common man and woman.

“He only seemed to listen,” declared Iman despondently. Iman is one of those ordinary Iraqis who met the president face to face and spoke with the leader privately.

Iman was a dedicated Iraqi nationalist, although not a Bath Party member. She was convinced that Iraq could achieve much, much more. She used opportunities with her president to speak candidly about some of Iraq’s domestic problems. “He paid close attention to what I said. But he didn’t listen…to anyone.

Reviews

In my opinion, [Swimming Up The Tigris] is the single most informative book, article, or report I have ever read about Iraq. It is gripping, depressing, anger-provoking… a roller-coaster ride of emotions which, in the end, left me feeling embarrassed to be an American.

J.P. Marra

Aziz does away with the mind-numbing and confusing statistics that form the core of nearly every other writer’s work on recent Iraqi history. She doesn’t count the bodies; she doesn’t dissect the Iraqi society by religion or clan as many self-styled Mideast “experts” do. What she does is provide a sweeping portrait of Iraqi society from the late 80’s to 2003 through the eyes, ears, and voices of Iraqis who lived through these turbulent times. She lets the Iraqis—farmers, diplomats, mothers, students, military, etc—tell it like it was and is. She presents a devastating portrait of what it is actually like to live in a state of war in an internationally isolated country under relentless attack.

If you believe, as I do, that the war against Iraq is one of the most important issues facing people in the US and world-wide, then you must read this book.

Deirdre S.

Independent journalist Barbara Nimri Aziz traveled throughout Iraq, beginning in 1989 in the days after the end of the Iran/Iraq war and up until the most recent disastrous invasion and brutal occupation. Her quest as an anthropologist was to document Iraqi society. She became a reluctant war correspondent.

This book documents the terrible years of grinding deprivation that was Iraq under the deadly US/UN sanctions. Why look at that period? Because everything that is happening today is rooted in the merciless sanctions period where more than 1.5 million people perished unnecessarily.

Every family in Iraq was touched. Everybody there would never be the same. Aziz writes brilliantly and compassionately about the people of Iraq, the ones we never hear from. The ones whose destiny is tied up with ours so completely.

Barbara Aziz’s recent book Swimming Up the Tigris is an important addition to the scholarly analysis of the Iraq War, its origins, conduct, and uncertain aftermath. Most Americans assume that the days of colonialism are over, leading them to overlook the quite traditional colonial basis for the invasion of Iraq, to secure its natural resources and control its almost limitless commercial potential.

Karen F.

Barbara Aziz’s exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with Iraqi people break through the clichés and illusions common to the mass media. Her warmth and compassion bring us face-to-face with the reality of modern warfare and the inevitable price paid by ordinary people in Iraq and other trouble spots around the world. Great powers may continue to intrude on vulnerable nations like Iraq, but the work of journalists like Barbara Aziz will make it difficult for them to win the hearts and minds of the world community. In the absence of popular support, aggression is unlikely to prevail.

The writer William Gass once described a book as “so good you don’t judge it, it judges you.” Swimming Up The Tigris by Barbara Nimri Aziz is that kind of book. Like most other writers on the Middle East I have focused so intently on America’s two military invasions of Iraq that I misjudged the near-fatal impact of the economic sanctions on the Iraqi people.

Aziz resembles the Nobel Prize winning novelist Toni Morrison in her refusal to accept the obvious answer to any question. (Has anyone but Aziz argued that the sanctions and embargoes hurt Iraq more than the bombs?) Another thing Aziz has in common with the magnificent Ms. Morrison is her uncanny ability to find the truth in terms of what is not there. Example: One of the most beautiful and harrowing chapters in the book is Aziz’s observation that the defining characteristic of Iraq’s playgrounds is the absence of children. (Just silence.)

Swimming Up The Tigris is required reading if we want to avoid the same mistakes with Iran we made with Iraq.

Ron David

As a social anthropologist, Barbara Nimri Aziz does not write a political diatribe. A keen observer of human societies, she examines, for example, how important education is to Iraqis, what role women play in Iraqi society, what kind of medical system is available to Iraqi citizens, how Iraqis coped with twelve years of devastating sanctions, how they are affected by the American occupation of Iraq.

Included in her role as social anthropologist is not just observation but participation. With a gift for friendship and an ear for story, Aziz empathetically introduces her readers to individual Iraqis whose afterimages have “staying power.” For those of us who have not traveled to Iraq, Aziz succeeds in giving her readers the haunting vicarious experience of having seen the tragic destruction of this ancient society as if with their own eyes.

Suzy Kane

Selected Articles

by Barbara Nimri Aziz July 2, 2025 What further avenues help us to reach Palestine? We witness repeated attacks and compounded injustices against unarmed Palestinians, day after day….

June 14/2025 by BNimri Aziz. If it would help awaken others to end atrocities and extinguish your own fear of being personally slandered, would you speak out like…

by BNimri Aziz June 14, 2025 Should I, or shouldn’t I? Can I, or can’t I? I may be alone. No villager who had accompanied me to protests…

by B Nimri Aziz. May 2025 Carried by Counterpunch “Starving children”, if you didn’t deduce the urgent it. (No illustrations necessary.) Starving Palestinians – of all ages. Not…

by B Nimri Aziz April 21, 2025. Carried by Counterpunch “Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk” is the title of a soon-to-be-released film featuring photojournalist Fatima…

by BNimri Aziz April 26, 2025 Moses Baptiste’s family laid their brother to rest on April 17th. But the Roscoe resident’s death leaves many unanswered questions Rockland town…