by Barbara Nimri Aziz, 06.19.23 (published in Nepal 06.17.23 by ekantipur)

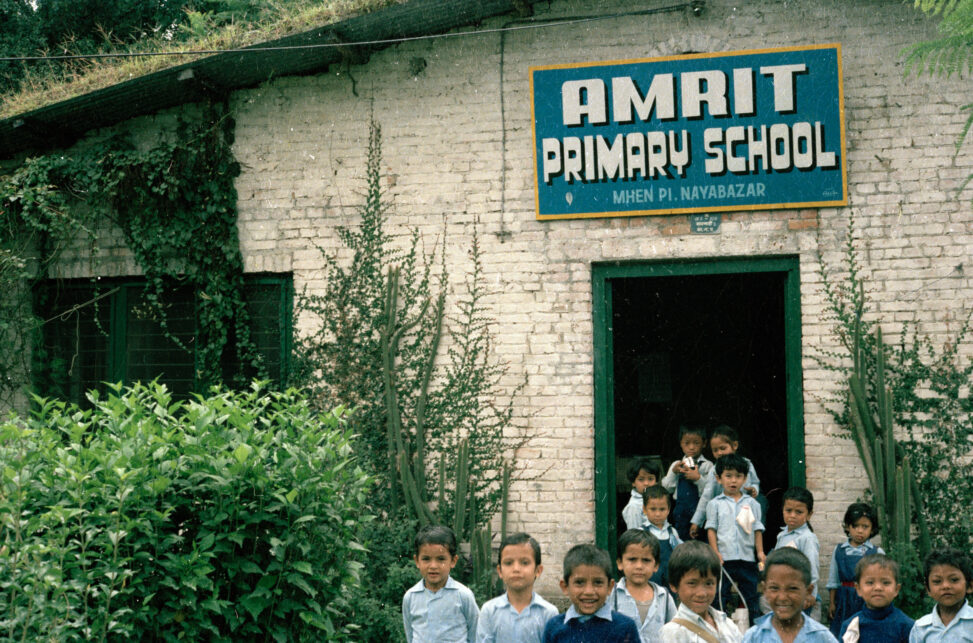

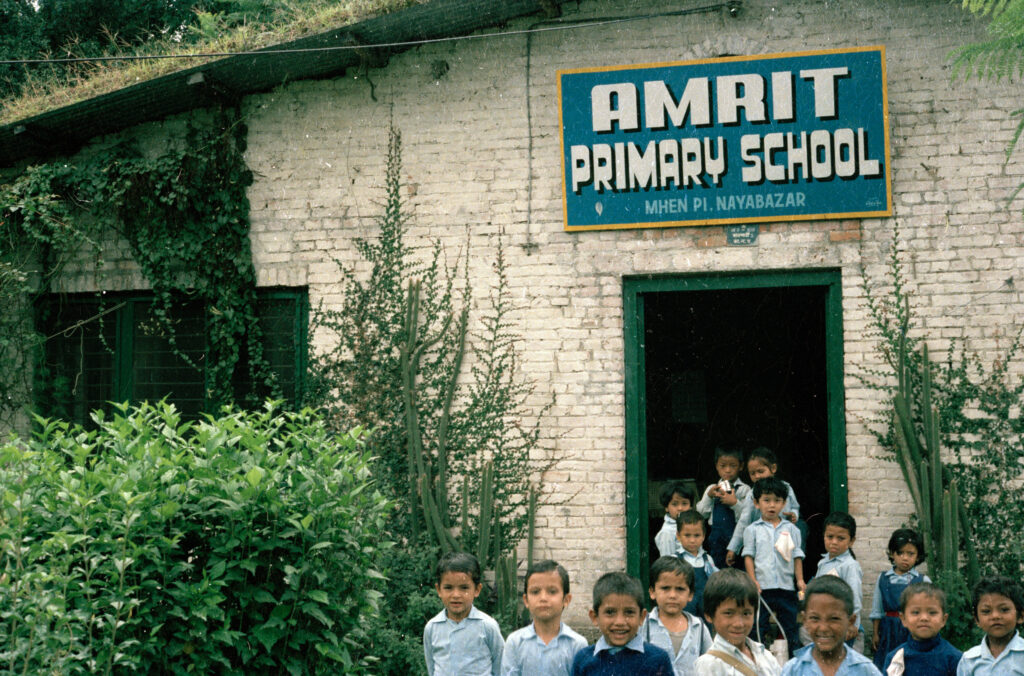

In 1983 when Sukanya Waiba and her sister Parijat Lama founded what’s now known as Amrit Secondary Boarding School, it was simply Amrit Primary School. It was the only school in that corner of Kathmandu Valley. You might not easily have found it, surrounded as it was by rice paddy and high, leafy trees. It sat sheltered below Mhen Pi promontory at the end of Naya Bazaar and on the edge of the capital. Today Mhen Pi is a crowded, popular neighborhood with easy access to the city center. Heavy traffic moves around it as new suburbs expand far beyond the sluggish Bhagmati River nearby and the old Ring Road a little beyond that. (The now motorable way between the school and the river is called Parijat Marg.) Passing there, you can also catch a glimpse of the Parijat Smitri Kendra, erected almost fifteen years earlier, in honour of the poet. It’s an active literary center for Kathmandu nowadays.

Today, in contrast to 1983, thousands of private schools are open across the country– in villages as well as towns. This is partly due to declining standards of education in government schools. It continues despite ample funding from the ministry and regardless of favourable benefits for their teachers.

As far as I remember, Sukanya Mam’s goal in setting up Amrit was not a reaction to government standards. She and Parijat wanted to offer a learning-place for the neediest children in their neighbourhood. They knew that some families might not send their children even to public schools. (After all, government schools for everyone were only introduced after 1970.)

Looking from their home to across the river, they could see rows of shabby huts sheltering poor migrant families newly arrived in the valley. Children there would not be educated without help, they expected.

Added to the sisters’ educational goal were their socialist ideals. Nepal’s ruling monarchy may have opened schools, but those would not want activists like Sukanya and Parijat joining them.

Besides welcoming neighborhood youngsters to their classrooms, Amrit admitted the children of their comrades who, like them, dared to oppose the monarchy. The parents of some were in jail; others had been forced into hiding.

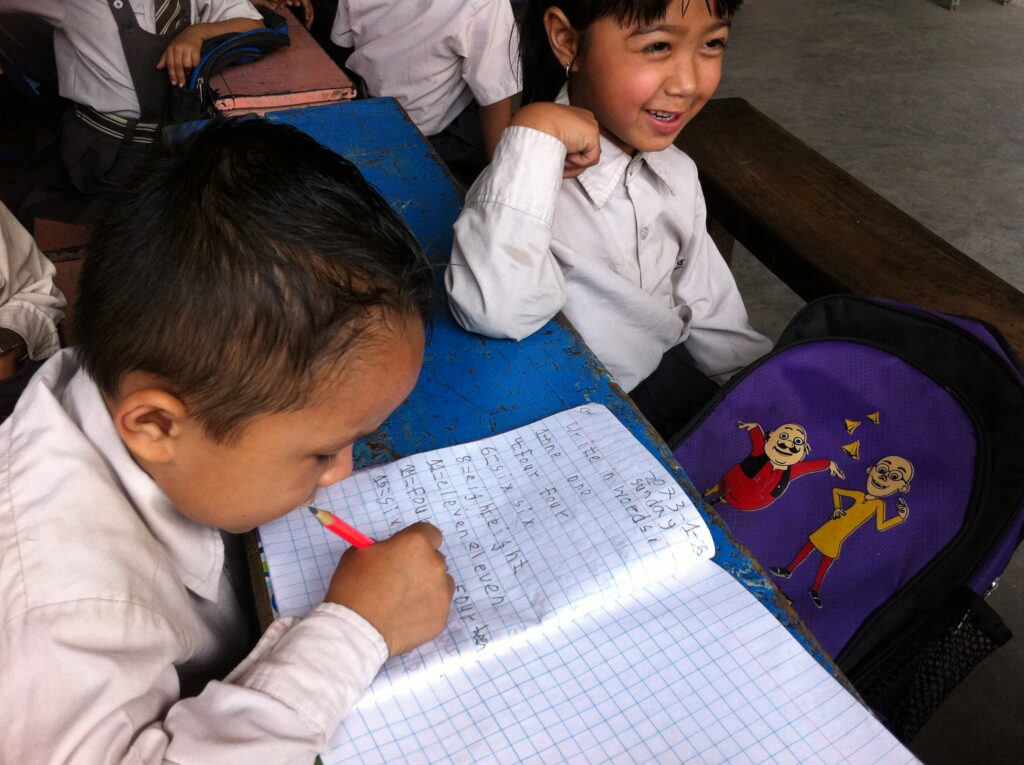

Both women were particularly aware of the economic and social circumstances of their young wards. Anytime, as we sat talking together, when an Amrit pupil passed us, or when an incident came to mind, Sukanya Mam offered details of an individual child’s abilities and their family life:—a missing parent, an orphan, a child whose father had beaten her mother who laboured alone to feed the family, a child whose mother had run off, a youngster whose only parent was in jail, a village girl sent to the city to live with an aunt. On and on.

When the director singled out a boy or girl– 6, 7, or 8-years-old– she called them from across the yard to greet me. Each stood proudly in their sometimes oversized but clean, blue uniforms and smiled, eager to use newly-learned English words. In recent years, after she retired as Amrit’s director, Sukanya Mam, looks out over the schoolyard and randomly points out to me one or two children. Again, she shares their academic rank and the family background. (Not their caste, but conditions in their home.)

It reminds me how Parijat Lama would beckon a teacher’s aide or a canteen worker and introduce them to me. She would explain how the woman had arrived penniless at their door, seeking shelter and comfort after escaping some danger. Or how, after a few years studying here, she succeeded finding a good job. Amrit became a place for the needy and lost, an anchor in a storm, a place they might temporarily secure work, find a place to sleep and a meal. For someone without a family or whose parents lived far away, these sisters offered lodging. Sometimes a child stayed for months.

When I visited their cottage, I myself often stayed overnight with the two sisters and Sukanya Waiba’s son, Nima, in their home-school. It was here, among these women and their pupils, where I really learned the political realities of life in Nepal.

I was fortunate. Normally, visiting scholars or tourists would never have such an opportunity. In those years foreign visitors feared associating with leftist nationalists. We were warned to stay far away from anyone daring to criticize the monarchy.

When I initially came here to meet Parijat, it was in connection with our shared admiration for the early 20th Century poet and rebel, Yogmaya. We talked for many hours in her simply-furnished room while children passed here and there, the sound of their recitations and gleeful shouts brightening the landscape of this sheltered corner of Kathmandu.

Amrit first opened for children in that small, brick cottage with only four rooms– the same location near the river where you’ll find it today. The school was set up inside the sisters’ residence. They put aside one room, then another. They set up a few simple benches to make the classroom. I believe they themselves were Amrit’s first teachers. They and other teachers too, were dedicated women and men whom they drew from their own network. They knew that education among the poorest was essential; and they shared their socialist political philosophy as well.

Sukanya Mam launched the school– paying teachers a humble fee and providing meals for malnourished children– with personal funds she had earned working at The Ford Foundation. The family’s own needs were minimal: simple tea, meat only on special occasions, no snacks, no surplus supplies, and no school guard those days. If they needed to visit a government office, they walked. Or they took a local bus. Whatever they had at the house, they shared. Wooden boards were hammered into desks by helpers. The land around the cottage belonged to the sisters, of no commercial interest those years. Amrit’s pupils studied in the fresh air of lush, green trees, among paddy. Gradually, as the school grew and needed more classrooms, playground, washrooms and offices space was cleared meter by meter.

Today Sukanya Waiba continually receives news from many of the youngsters who began their education with her 20, 30, 40 years ago. If a dozen, or a hundred, or a thousand Amrit graduates could offer their memories of the school and of Parijat Mam and Sukanya Mam, their words would become a story of Nepal itself – a colorful bouquet of successes. Those students became proud parents of the new generation of modern Nepalis. If we explore Nepal’s national horizon for them, we would find hundreds of Amrit graduates who’ve become teachers themselves, who have opened businesses, who were once migrant laborers, who are nurses and dentists, civil servants, politicians and party activists, writers and journalists. Amrit will be proud of every one, whatever they did and wherever they went.

Just as these pioneer women reached out to neighbors and others to learn which homes had needy children, they called on friends to support their efforts. A board of trustees was formed. Friends personally sponsored one or more students, covering the cost of school fees, notebooks and perhaps a school uniform.