By BNimri Aziz 04/27/23

It was only when I started reading a collection of this remarkable African leader’s prison letters (records from 1962 to 1990) gathered in a judiciously edited 600-page book that I began to grasp the powerful character behind the freedom fighter, prisoner and South African president.

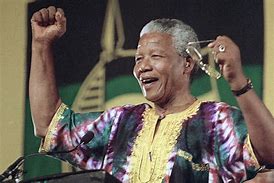

Many of us have seen the films “Long Walk to Freedom” and “Mandela”; perhaps we’ve read one of his biographies, autobiographies, collections of essays, and consulted quotations and websites devoted to Nelson Mandela. So we understand a lot about this man’s political and ideological struggle before his incarceration and after his election as South Africa’s president in 1994.

But this collection of 255 prison letters offers another layer of the man’s personality—one that reminds us of a community beyond his ANC comrades, namely, a family of individuals with whom he was intimately and regularly involved. He carried these people with him into captivity throughout their 27 years of separation. They live with him within his letters.

Perhaps because of the editorial demands of translating some of the correspondence, locating documents from various sources, clarifying names, and arranging permissions The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela was released only in 2018 (Liveright Publishing, NY). The volume’s interest to historians, civil rights activists and all who celebrate his achievements is clear. Yet within this chronicle, as I read letter after letter, I discover new dimensions of its author. I didn’t expect to learn so much more about Mandela. Not conditions of Robben Island, Pollsmoor and other jails where he was captive; I’m enjoying a deeper insight into the man’s personality and thereby into his ultimate triumph.

To start, from excerpts of just four items from the early years of Mandela’s imprisonment at Robben Island, here’s a hint of what this treasure offers.

To Commissioner of Prisons Pretoria (undated letter but possibly October, 1965; ed.) I am grateful for the concession you made on 13th October, 1965 when you informed me that you had no objection to us exchanging study books among ourselves. This relief will considerably reduce the expenses for prescribed text books … …if the privilege to study us to be of any value, certain conditions are absolutely essential.17 Feb, 1966 Darling, (wife, Winnie Madkizela-MandeIa) I should be pleased if you would kindly instruct Mssrs. Hayman and Aronsohn not to proceed with the action against the prison authorities. On 8th February, I had an interview with the chief magistrate of Cape Town who came on the instruction of the Secretary for Justice…I have passed the Hoer Africaanse Taaleksamens and have now enrolled for Africaans-Nederlands Course I with the University of South Africa… my funds have run out…please do not pay from your account... Tons and tons of love to you darling and a million kisses. Tell Thembi, Kgatho, Maki, Zeni and Zindzi that I miss them very much and send them my love, devotedly Dalibunga

31.8.66 The American Journal of International Law

Dear Sir: I have not received the July 1966 issue of the American Journals of International Law. Presumably because my subscription has lapsed … … I am preparing to write an examination in public International Law shortly and should, therefore, be pleased if you can kindly advise me…

(see further passages below)

Perhaps in the latter part of this chronicle, Mandela will detail his ill treatment and conditions of imprisonment. Yet I’m not inclined to rush through the remaining 300 pages to search for that. I remain absorbed in each letter, and thereby in the routine but precious lives of his community: he spares no details in comforting and advising those outside how to overcome their daily struggles and ambitions; he offers concrete help to friends and relatives, including those abroad; he directs his attorneys and gathers financial support for his children’s education; he advises his wife through her trial and prison ordeal; he patiently writes prison authorities requesting attention to what he knows are his rights, even as a condemned man; he negotiates the completion of advanced law degrees and learning Africaans, the language if his oppressors. These letters overflow with respect and affection, detailing Mandela’s goodwill and, always, his expectation that he will meet them soon.

Wisely, this volume’s editor does not try to summarize the 27 years that Mandela’s epistolary record covers, but offers useful notes on the dozen or more collections from which these were drawn. In barely 20 pages of introductory remarks, we are given essential background: the stages of imprisonment, limitations on meetings with family, speculation regarding missing letters– those confiscated, never delivered, destroyed, or discovered years later. With this framework, the content of the letters in this volume becomes more remarkable. Mandela never knew if his letters would reach their destination, why others’ replies went missing, why a meeting was cancelled. Artfully, perhaps cunningly, he copied most of his letters before sending, and as evident in this collection, he refers his correspondents to earlier letters he’d sent and to whom. Tracking some of his undelivered materials was again a special contribution of this volume.

All the letters possess a remarkable intimacy, whether they’re recording Mandela’s feelings or relaying specifics about the lives of family and friends, or if they’re directed to officials. He knows of course that everything is censored.

One might be tempted to fast forward to the more dramatic entries recording his mother’s and son’s death and his wife’s imprisonment. Still, each letter has its strength and genuineness. Each missive, even those about his law studies or his damaged glasses, is revealing. He is never the victim, and apparently never bitter. His long report to the Robben Island Commissioner in July 1976 about censored letters, irregular visits, and other conditions is a skillfully composed document. Comforting his daughter or reporting administrative defects of the prison, his exceptionality seeps out of every line. More than his oft-quoted words, this collection explains Mandela’s positivity and clarity of mind.

This is not a collection to be skimmed through. So, while perusing the final 300 pages, expecting to be equally captivated by every entry, here are a few more excerpts from some letters from Robben Island between 1964 and 1970.

8 September, 1966. The Commanding Officer, Robben Island

I have broken the lens of my reading glasses and I should be pleased if you would kindly arrange for the glasses to be sent for repair to …

11/2/67

Dear Cecil (former Golden City Post Editor). I need R150.00 for my studies. May I exploit you. During the last four years I parasited on Winnie. She has been out of employment since April ’65… I must burden you with another… my son Makgatho, was expelled from St Christopher’s Manzini, apparently after a student strike there. He now attends a local school. I fear that the sudden change may affect his progress. He may also feel lonely ad unhappy….I was happy to know of the rapid growth and expansion of the enterprise you have piloted so skillfully…looking forward to the day when I will again see you and enjoy the happy moments we have spent together in the past…. PS please inform Winnie that in arranging the next visit, she must give preference to Madiba or Makgatho…

16.11.69.

Dade Wethu (Winnie Mandela) I believe that on Dec. 21, you and 21 others will appear in the Pretoria Supreme Court under the Sabotage Act…it would seem that you would require me to give evidence on your behalf….. unjust and contrary to the elementary principles of natural justice to force you to start a long and protracted trial on a serious charge without arrangements having first been made for us to meet… there will be those whose chief interest will be to seek to destroy the image we have built over the last decade. Attempts may be made to do now what they have repeatedly failed…

1 May, 1970 (To Mandela’s youngest daughter, Makaziwe)

My darling: I am pleased to hear from Kgatho that you have passed your JC examinations and that you are now proceeding with matric. The good progress that you are making in your studies shows that you are a talented and keen student… I hope that in your next letter it will be possible to give me the symbols that you obtained in each subject… in your undated letter which reached me on the 15th November last year, you say that you no longer want to be a scientist because funds will not be available… I did hear that mom Winnie is in jail and I agree with you that it will be a longtime before she comes out. …I cannot give you a clear and straightforward answer as to who is taking care of the children. But you, Kgatho, Sisi Tellie, Makazi Niki, and our numerous friends are there to look after them.

8 June, 1970.

Our dear Ma In July 1967 Major Kellerman, then Commanding Officer of this prison, gave permission for me to write you a special letter of condolence on behalf of all of us here on the occasion of the passing of the late Chief (Albert Luthuli, former president-general of the ANC) Under normal circumstances we would have certainly attended the funeral to pay homage directly to the memory of a great warrior as he passed from the stage into history…