March 4, 2021 B Nimri Aziz

Before trekking through open Himalayan valleys, tourists might stroll along Thamel, Kathmandu’s congested quarter of hiker hostels, bakeries and cafes. They’d pass a landscape studded with bookstores, and perhaps pause to flip through glossy picture books and Tibet-wisdom manuals, lingering to inspect storybooks or development reports stacked on higher shelves. On exiting, they’ll pass a rack of 3 or 4 English language dailies.

Only visitors really curious about the how the nation’s citizens think and feel might search out a volume of poetry or a novel by a local writer. If so, they’ll find a surprising number of Nepalis choosing to pen their experiences, their struggles and their dreams in English.

Nepali prose and poetry in English is of course far less than exists in Nepali language which on its part has grown enormously in recent years. But there’s a correlation between literature in the two languages going back to Nepal’s most widely read and revered poet, Laxmi Prasad Devkota (1909-1959). Although Devkota did not live beyond 50, he penned no fewer than 24 volumes of essays and poetry, including epic poems. His work is recited and discussed by Nepalis young and old today.

Devkota was highly proficient in English as well as learned in Sanskrit and Nepali. Kumari Lama, Assistant Professor of English, Tribhuvan University and a literary critic, speaks fondly of her country’s supreme literary figure: “He was my introduction to English literature; I decided to pursue this field of study as a result of that exposure.” Besides translating other Nepali authors and rendering Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ into Nepali, Devkota composed in English, e.g., ‘Bapu and other sonnets’ in tribute to Mahatma Gandhi.

Devkota was writing and translating seventy-five years ago. Nepal was barely connected to the English-speaking world then, and English was exclusive to privately tutored children of royalty and high officials.

Lecturer, translator and poet Mahesh Paudyal also attributes to Devkota his introduction to English literature. “I read his English essays and poems in my first university course in non-Nepali literature.”

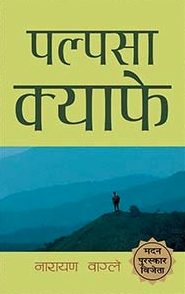

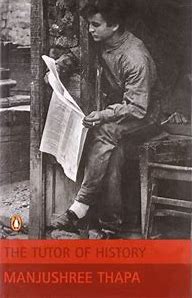

Today we find a new generation of Nepali writers among the ranks of international authors of modern English literature. Kumari Lama highlights Manjushree Thapa and Samrat Upadhyay for pushing the boundaries of Nepali creativity into English. With stories set within Nepal and in the diaspora, these authors attract an enthusiastic Nepali following while also winning a solid western readership. They are joined by Peter Karthak, Shushma Joshi, Sangeeta Rajamajhi, Abhi Subedi, Niranjan Kumar, and Narayan Wangle whose Palpasa Café is translated into no less than 12 languages. Now established in the international literary community their writings offer a compassionate, personalized experience of Nepal which is simply absent in ethnographies, touristic journals and development studies of the country.

Perhaps from Devkota’s inspiration, we find Nepali-language literature and English literature by Nepalis still interconnected. Thapa, Nepal’s most widely published author in English, is also engaged in translations from Nepali to English, e.g. This Country is Yours, a collection of 49 authors.

Online literary platforms feature Nepalis composing in English alongside translations of stories, poems and essays penned in Nepali. Publiknama is one; another is TheGorkhaTimes, recently launched by Paudyal and colleagues. Executive editor Himanshu Kunwar notes that readers access TGT from more than 100 nations.

La.lit literary magazine is a handsome production by Nepalis in the U.K. which features creative writing (including translations) by Nepalis across the world.

Nepal itself hosts venues like Himalayan Readers Corner in Pokhara and Martin Chautari in Kathmandu. The Open Institute directed by writer Muna Gurung and Aahwaan with a focus on women also sponsor literary discussions and workshops in both languages.

Considering the strong Indian presence in Nepal through film and other media, one might have expected India’s celebrated English-language authors to have impacted Nepal in this field. While this may have been so earlier, Ms. Lama and Mr. Paudyal minimize Indian influence today.

Kumari Lama points to domestic political factors behind the groundswell in literature within Nepal. “First, when democracy took hold in 2008, we had an expanded opportunity for free and open dialogue. Second, Nepal’s many indigenous minorities eagerly began writing about their aspirations and history which were earlier suppressed or altogether banned.” Paudyal agrees the nationalist movement that ushered in free speech was a great impetus to creative writing.

Global factors and the internet are impacting Nepal too. “We communicate with sister Asian cultures through English; it’s our common medium with Bangladesh, China, Korea, Japan, and Malaysia. That includes literature,” explains Lama.

As a professor of literature, Lama sees fewer students enrolled in university English Literature programs, whereas more Nepalis seek to master English for economic reasons. Whether they work inside Nepal or have ambitions to study overseas, being able to converse in English is essential.

And if the millions of jobless in search of work in the Arab states or Malaysia know no English when they set out, many return to Nepal with a conversational knowledge of the language.

To appreciate just how embedded and promising English literature in Nepal is today, we can consult Manjushree Thapa’s A Translation Manual: To Bring English Literature to Nepali Readers published in 2002 and Paudyal’s 2017 survey Nepali Literature in English. Finally, Kumari Lama’s 2017 review What they are writing in English offers an excellent comparative critique of authors (and others) discussed above. Or on your next Himalayan trip, add a Nepali novel to your souvenirs.