[Originally published in “Anthropology of Tibet and the Himalaya”. Editors, Charles Ramble and Martin Brauen; Ethnologische Schriften Zurich, ESZ 12, Ethnological Museum of the University of Zurich 1993]

In East Nepal, early in this century, an extraordinary uprising took place. Led by a woman of exceptional ability, it directly challenged the Rana regime and the Brahmanically-determined power structure prevailing in Nepal. Yet that uprising and the personage of its leader are almost totally obliterated from the historical memory of the Nepali nation. In this article I try to throw light on that obscured history. At the same time I reflect on some of the challenges we face as scientists as scientists exploring the role of women and peasant people in our lives and our work.

As many people familiar with my research will know, a decade ago I became interested in the experience of pilgrimage in South Asia. I made several journeys to specific Himalayan sacred places and wrote about them (Aziz 1982; 1983; 1987). My curiosity about pilgrimage originated when, sometime earlier in Nepal, I witnessed Tibetans’ relationship to the relics of Langkor; pilgrims drew personal power from a history told in an account of a set of stone relics carried to safety from Tibet to Nepal in 1959 (Aziz 1979).

Before that of course like anyone who travels in India or Nepal, I was familiar with the sight of women and men en route to a monastery, an alpine lake, an enchanted cave, a riverbank, or the residence of a holy person—to encounter the divine.

In 1980 when I began to think about this experience more systematically it was also a time when I began to reflect on the limits of my past approach. It was essential to articulate my own voice within the anthropological texts I was interpreting, Ethnography, I decided, could not exclude self-reflection.

By that time, I had also simultaneously been convinced by the revelations from our feminist scholars of the 1970s, of the misogynist character of modern social science and history. In media and political life, in academic research and in language, in virtually every interpretive field, not to mention daily interactions, there was indeed a powerful selective exclusion or obfuscation or devaluation of the experience of women. Without really needing more evidence than studies available by 1980, I understood what the new feminist scholars were claiming. It left an indelible mark on me and I could never again view human relationships within the same narrow limits.

In this state of mind, I pursued pilgrims through those mountains we know so well. Departing eastwards from Solu in the hills one rainy September, I found myself in the valley of the Arun River. It was a steamy hot, jungley place cooled only by the breeze coming off the icy water.

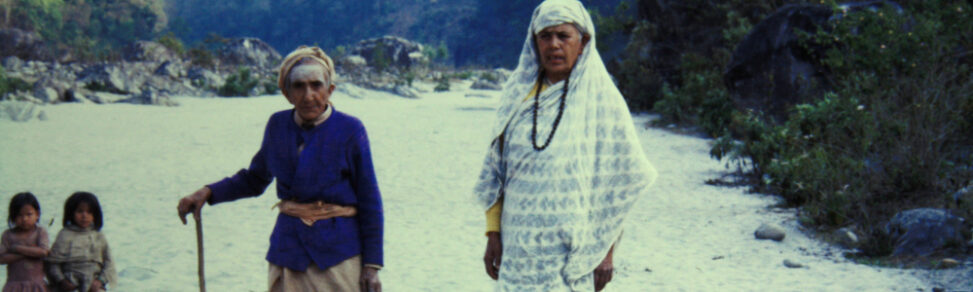

Well accustomed to the ready hospitality of Tibetan nuns, I stopped at another community of women there on the banks of the Arun. In this case, it was a shrine Manakamana, home to a group of sanyasi or bhaktini—ascetic Hindu women.

On my first night at the temple, lying in the open shed, I heard the soft roar of the great Arun River and the shrill of the night insects. Woven with those sounds in the air was the ladies’ singing. I did not know Nepali well and I was familiar with Hindu prayers only as a tourist. But I sensed that something special was embedded in those words. Called Hazurbani, they would gradually lead me to the life and work of their creator, a remarkable woman known to her people as Shakti Yogmaya.

What I learned about Yogmaya, I want to share with you now. I make no claim that her life had any bearing on Tibetan people. She worked with Hindus- Brahman and Chetri—whose activities and history are beyond the scope of a seminar on Tibet and the Himalayas. Today however, the life of such a person as Yogmaya is relevant to any peoples residing in this region. Nepal has recently experienced an unparalleled public uprising with revolutionary implications. What happened in that nation this past spring (1990) raises questions about political resistance and leadership in the entire area. Today, any history of dissent existing in Nepal, past or present, is of immediate concern. As Yogmaya was herself a dissident, her efforts or accomplishments must be examined in any discussion of this nation’s political history.

The 1990 spring uprising in Nepal was a massive nationwide movement which took a form m unique in the world. Although my concluding remarks will touch on this event, I am interested in it only in light of past rebellions. In this paper, I confine myself to that earlier revolt. Yogmaya’s campaign may not have had the same success; it was certainly local by comparison. But it was significant in itself. And perhaps, once we understand the past, we may recognize in Nepal’s history similarities or links with the more instance of dissidence.

Before proceeding, I want to pose four questions. Such considerations normally come, with their answers, at the end of a scholarly paper. I do not have answers for the questions I raise. Appearing here at the outset of my account, they may assist readers in judging the material as the story unfolds.

- Is it significant that this revolt occurred in East Nepal an area not far from the Limbu land, and also close to Assam and Darjeeling in India where political dissent has a long history?

- Why was the movement joined only by Brahman and Chetri people in this region? Why did it not spread to the Rai and Magar people of the area, populations who were more exploited and who were also known to have endured far greater injustices than the higher case Brahman and Chetri?

- Could this movement have been part of the Assam-Bengal resistance movement, largely directed against British rule that emerged in the earlier half of this century?

- How was the resistance movement led by Yogmaya so thoroughly removed from Nepali historical consciousness?

Now to our heroine. Yogmaya belonged to a Neopane Brahman family in the village of Kulung. This same locality became the centre of her operations and it involved several eminent Kulung families . Kulung (on the ridge) and Majwabesi (at the riverside) are half a day’s walk from Khandbari, the present district center of Sankhuwasabha, from Chainpur, a major town in the eastern hills of Nepal, and Bhojpur. (Bhojpur town has a well known history of dissent.)

The earliest comment on Yogmaya’s life was an act of rebellion: it was her elopement. She came to others’ attention when she ran off to Assam with a lover. This was of local interest because she was a child widow, and because the man she loved was not a Brahman. He is nameless and details of her life with him beyond the boundaries of Nepal are not yet well known.

Confining my research to Nepal, what I learned about Yogmaya happened only after she returned to the run Valley. Her followers, it seemed, had little interest in what happened to her in India. For them, her story begins around 1930. Why she returned we cannot yet say, but she made a clear decision to do so, bringing with her a daughter, the child of that union, a girl whose name was Nainakala.

Yogmaya’s family had remained in Kulung, and when she arrived at their door, she was not warmly received by her parents. Her brother and his wife Ganga Devi, did welcome her and they became very close.

Together with Yogmaya and Nainakala, this couple became the core of the movement that reached its peak with perhaps 2,000 members a decade later.

The first assigns of Yogmaya’s genius appeared in her poetic hymns. These were later to be known collectively as the hazurbani. They are the utterances I heard when I arrived at the riverside temple where her followers lived. They were the sparks which ignited my curiosity and led me to the events of Yogmaya’s extraordinary career. They contained the kernels of her teachings and symbolized both her appeal and her talent.

Early in what I would call her mission Yogmaya began to compose poems. At first, as far as I can tell, these praised nature, the river, the Himalayas. In style they were close to the devotional bhajan.

Hailed as supreme, our Himalaya

Feeds the waters.

Arun emerges; with Barun it runs

Down, down they mingle into Irakwati.

A graceful bird’s song

Captures my heart;

Oh gentle river’s whistle

Caresses it.

Others of her compositions are playful songs associated with her austerities and yogic powers.

Parting the year in two,

Perform your rites;

In summer, favour a scorching fire,

In winter, delight an icy river.

Fear execution? Why?

A body is mortal after all.

Here by divine grace,

Later, on some pretext I shall be gone.

Only later it seems, did her verses become virulently political.

Greed and avarice consort with gluttony;

It’s not an occasional union.

If the raj in his palace never looks,

There’s nothing to attend the poor;

Not even occasional justice.

They mix greed into our incense

And we burn it.

Odious smells arise.

How horrified the gods! They plead.

Wealth cannot multiply without fraud,

None can say: ‘not so’

The rich make pilgrimage to garner benefits,

We poor go in search of our souls.

(Translated by Parizat and Morari Aryal)

At present no dates are attached to these poems. It is not absolutely certain if the poet created any of the differences we see in content at various periods. Research is needed to say for certain if the political poems came later. From such research we may also ascertain what outside (Indian) influences there were. I have assumed that the political poems came later because she herself adopted a more assertive and confrontational general strategy.

The hazurbani reproduced here were printed, they appear in a book of about 100 poems, a small collection published in Darjeeling in 1940, not long after she died. The booklet containing both political and purely religious examples, and the accompanying biographical note, found their way back to Nepal. it seems however that they did not come to public attention.

The survivors of the movement who offered me a copy of this book, maintain that many more of the hazurbani they recite have not yet been written down. If interest in Yogmaya grows researchers may still be able to harvest more examples from recording the recitations of these women and men. (the tape recordings I made from the women I met can be made available for comparison.)

Anyone who knows these hazurbani maintain that they were exclusively Yogmaya’s, composed spontaneously , uttered in a state of trance. I have no reason no doubt this. Comparing them to poems (all without political content) collected from the disciples, Prem Narain and others, and bhajan sung by the yogis in the region, the special quality of these verses is easy to recognize. Moreover their rhythm is also distinctive. After her daughter was educated and these compositions became a feature of her teachings, Nainakala copied them out. Her aunt, Ganga Devi, was the person who created the special rhythms in which they were sung.

During the first years after Yogmaya returned to Kulung region, she did not spend much time with her family. She left her daughter with her brother and his wife who educated the girl. Meanwhile the emerging revolutionary roamed the hills of her country. We know from some of the hazurbani and personal stories that her pilgrimage took Yogmaya to Khembalung cave nearby, to the border of Tibet and to other holy places.

That was, I think, the time when she began to understand the beauty of her land but also to witness and think about the exploitation of her people and to feel compassion for them. We can fairly assume that her experience in Bengal, at a time of political foment there, was an important foundation; it surely contributed to the development of her own philosophy. But we have no concrete evidence of this and await research from Bengal itself before we can precisely trace the link.

These women who taught me about Yogmaya, her surviving followers, say her teaching was unique, that she was nobody’s agent. They deny that she was a member of a particular party or sect. According to them, she did not belong to any wider political movement. Correspondingly, working with them, I was unable to find specific evidence of ties between Yogmaya and other reformers in the region, or of influence form India’s political struggle, so active at the time she lived in Bengal. We should assume some degree of outside influences. The Nepali scholar Janak Lal Sharma claims that Yogmaya belonged to Joshmani, an anti-Brahmanical sect influenced from Darjeeling, India. Yet, according to Sharma, Joshmani was non-political in its nature and aims (Sharma n.d)

Where then did our heroine receive her political education? To locate the roots of her mission more research in India is needed. Doubtless, investigations into those parts of India where we know Yogmaya travelled should be useful.

Meanwhile, why do we not take the evidence offered by Yogmaya’s followers? Involuntarily, I found myself resisting this obvious approach. I searched beyond Yogmaya. In the course of this research I often said to myself: “but she must have learned this from elsewhere; she must have had a teacher.”Unable to shed the common biases of scholars, I rushed from the Arun Valley to Kathmandu to consult historians, politicians and poets about this remarkable woman. In some cases, individuals such as (Prime Minister) BP Koirala, and a former minister from Kulung, D.B. Basnet, affirmed her existence. But that was all. To learn facts, I had to return to the Arun Valley and speak to the bhaktini. In the course of this exercise, I became aware of biases I had inherited in my training as a social scientist. I admittedly have difficulty imagining that a hill farmer, and a woman as well, can independently evolve those political positions and philosophies. Yogmaya’s positions were reasonable and logical. They need not have come from some higher authority. Why could she not have arrived at her position based on her own intelligence and resources?

Indeed when I read the hazurbani, I am convinced she could have.

Lord Prime Minister, hurrah!

Again and again, I applaud you.

Like a spider who neither ploughs nor sows

Yet swells and swells still more.

Nowadays O Brahmans, live as you wish;

Like lords you can plunder the poor,

So corrupted you sell your trust.

So deep the roots of your greed.

Fat bellies burst

And those bribes ooze out

To poison you.

So savor your riches a little longer.

Simple as they are, these compositions are indisputably profound. I have no doubt that they had the power to inspire rebellion. The hazurbani remain my primary sources. Essentially they are anti-Brahmanical; they oppose the Brahmanical economic and political grip on society, its caste distinctions, and the selfishness of those in power.”It is all contained with the hazurbani” say her people.

Examine these examples and compare them with political speeches, scholarly philosophies , theories and the poems of others. Scholars and poets in Nepal tell me that nothing comparable exists. The same is said of the musical rhymes that carry the hazurbani. They are unlike any Nepali folk songs and they are not really in the tradition of the hymnal bhajan. They can be explained only by the genius of their creator.

Yogmaya, before she actually began to advocate reform, spent several years in retreat. She stayed alone. It was in a cave, Manohar, no more than an overhanging rock above the place she would make the centre of activity. At first, I believe, she was shunned by most of the villagers in her community. She had, after all, broken the rule prohibiting widow remarriage. Furthermore she had crossed caste lines.

Later, after she became an accomplished yogi, meditating in this cave, people temporarily forgot about this. Because of the power over nature that she demonstrated, she won the respect of the villagers. They began to bring food to her and witness her strange physical powers, the tapasya, or austerities.

Her really active period of dissent began when she emerged from this cave. It lasted just a few years, perhaps no more than four, from 1936 to 1940 (B.S. 1993-1997). If one understands what an accomplished yogi is capable of, it is easier to appreciate Yogmaya emergence from reclusiveness to political activism. We should remember the cultural climate as well. As Dr. Harka Gurung remarked of Yogmaya’s strategy, “In a political system where authority itself is religiously sanctioned, it is necessary that any opposition to government also takes a religious form”. No resistance could get very far otherwise.

One hazurbani declares “there is no difference between fire and ice”. Losing her fear of death, this rebel also lost her fear of the Raj. Losing her attachment to her life, she could confront any trial. Moreover she acquired the power to see how social differences are simply creations. She sang “I am the babe in your lap/you are the child in mine/ your eyes have tears just like mine” Advocating social equality at that time was indeed rebellious and it called for tremendous courage. Anyone advocating such ideas faced the possibility of execution.

After Yogmaya defied nature’s power, she could also defy the authorities. Moving to the riverside at Majhwa, she began her political campaign in earnest. Nainakala her daughter, sister-in-law Ganga Devi, and Yogmaya’s brother joined her. Somehow, speaking against caste and Brahmanical abuse, she was able to gather local people around her. They recognized the injustices she spoke of; they felt things might be changed; otherwise they would surely not have persisted.

Within two years the moon-faced yogi had attracted a considerable community of men and women. It reached two thousand at its peak, with several hundred residing at Majhwa itself. Most of Yogmaya’s followers were Chetri or Brahman. None was poor. Only a few were former child widows.

Women and men in neighboring villages heard about the hazurbani and the miracles their creator performed; and they travelled to the riverside settlement to join that community. They took relatives along; not old parents ready to die but young girls and boys and their aunts and uncles. Whole families assembled around the yogi. Predictably, after some months, others in the area became alarmed. From the start there was resistance as well. Hearing about anti-caste ideas being promoted there, parents did not want their young people attending. They were shocked to hear of Brahman widows taking up residence with male members of the community.

Local criticism grew. But the movement did not stop. If anything it became more rebellious. As her following grew, Yogmaya became more forceful. She advocated what she called a dharma-raj, a term I interpret as “rule by justice”. With this slogan, Yogmaya directed her attacks towards the palace, to the dictator Raj, Nepal’s hereditary prime minister . Believing he might be pressed to accept and to introduce the changes she sought, she launched a series of appeals. The local people’s campaign may have been so successful that she felt encouraged to take this step.

By now Yogmaya had become a frequent visitor to Kathmandu and the holy Pashupatinath northeast of the city. A following of Brahman men and women, many of them from East Nepal who lived in the capital, gathered around her there. Others moved from Kathmandu to Majhwa, her centre on the eastern bank of the Arun River.

After her first appeal to him, Yogmaya was shunned by the Raj, although she may have had an audience with a secretary in the palace. There is hardly a doubt that the ruler was aware of her and her demands. Later, back in the Arun Valley, she dispatched Nainakala to Kathmandu to deliver another plea for dharma-raj. That too was dismissed outright. Yogmaya responded by intensifying her demands. It seems she sought no intermediaries. She directed her assaults to the ruler himself. Her fierce poems to the palace are grounded in the reality of the life of the oppressed: the bonded laborer; the child widow; the sharecropper; against the priest who recites, then collects his gifts, and the merchants who mix grain and sand.

Yogmaya rightly supposed that the dictator would never attack her personally. She knew the rule against Brahman murder. She was assured that no ruler, however ruthless, could commit this most heinous crime. Perhaps this protection explains why her earliest attacks went unanswered. Normally such a challenge to supreme authority was easily dealt with—by brute force, imprisonment and murder. According to Hindu law however, this Brahman troublemaker could not be killed. It was equally difficult to jail a yogi, and a woman as well. So her challenge was met with silence.

Yogmaya did not like this. Finally she decided on a strategy to force the ruler’s hand. She presented the palace with a bold threat: “Give us rule by justice, or we shall sacrifice ourselves”. Her statement was delivered in writing and it was signed by more than 200 of her followers. They specified moreover how they would burn themselves in a great fire by the river. Indeed, on the shore of the Arun River, members of her group had already begun to assemble logs for their communal pyre. The pile of wood had reached an immense, awful size, when one night, troops arrived.

Barely forty-eight hours after the palace received Yogmaya’s demand, it acted. Hundreds of soldiers were dispatched from Dhankuta and Bhojpur. They gave no warning. Many of Yogmaya’s people were captured. Others ran, fleeing in all directions through the forest and up the mountainside. Because the military commander had the list of names submitted with Yogmaya’s ultimatum, his soldiers pursued and sought out individuals in their homes.

Many escaped arrest; however the rebel leader was not among them. She, along with the other women captives were imprisoned at Mandir Temple in Bhojpur, the district headquarters. Most of the men were taken to the jail in Dhankuta, two days walk south.

The commanding officer at Dhankuta region at that time was Madev Shamshere Rana. In 1984 three years before he died, I met him and he confirmed that as head of the Dhankuta region more than forty years earlier, he himself had led those troops up the Arun Valley to capture Yogmaya. (Documents relating to Yogmaya’s rebellion, he said, were located in the district office. He suggested that legal proceedings had followed her arrest. But up to the time of this report, no corresponding file has been recovered. Efforts should be made to locate it since it may be one of the few official documents bearing directly on this episode.)

For months after this arrest, tension gripped the area. It was evident that the government did not know what to do next. The woman and her people could not be held indefinitely. Neither could they be killed. The several hundred followers in hiding were an unknown element whose actions could not be predicted. Not surprisingly the next move came from Yogmaya. The campaigner began to recite the hazurbani from inside her prison. Her fellow captives accompanied her. At Bhojpur and also at Dhankuta, it is said that policemen and their families gathered near the prison to listen to the verses. Sympathy for the rebels seemed to be growing.

More time passed. The government must have been desperately searching for a solution. The problem of holding the rebels was compounded by their social status. Not only were many of them Brahmans; they were also members of eminent families and that won them considerable public sympathy.

Eventually Yogmaya prevailed upon to agree to abandon her mission in return for her release. As far as we know, she agreed to abandon her demands and to disband the group she led. If anyone doubted that the accord would hold, they did not say.

The rebel leader returned to Majhwa and an ominous silence followed. She had not been released more than a few days when an announcement quietly circulated among the faithful. Each was faced with a decision. Early, about 2 o’clock in the morning of Asoj Ekadesi, seventy women men and children gathered at the riverside downstream from where they customarily assembled. Yogmaya was there of course. Nainakala and her uncle and aunt were in the assembly too.

Today Majhwa is a quiet bend on the great roaring Arun River. In a small mandir above the bank, beside a tree where she sat uttering her demands, a wooden arm chair is preserved. There is no photograph of her, no book, no urn of ashes, no relic bone. Most of the time, the mandir is locked. In the morning and again at sunset, some elderly ascetics, most of them women, the most feeble looking men and women you can imagine, attend the shrine.

“Oh those are some old bhakti”, the local people will tell you. “Old widows; they sing their prayers and will die there.”

But this was indeed the meeting ground of two thousand rebels, people who had hopeh for change, a leader of extraordinary courage, a person who dared to say injustice had to end. A visitor to Majhwa today can meet some of those survivors. It is still possible to hear the hanzurbani sung as well. And the temple custodians may lead a visitor to the sandy beach, to the round stone embedded in the bank covered by the high summer river. In wintertime it is easily exposed, lying just beneath the surface of the beach.

“This is where Yogmaya entered heaven”, they explain. “Sixty-eight of her devotees joined her; they followed one another into the river.”

Yogmaya’s body was never found.

A list of names is said to exist, names of the men and women who signed the paper after the master. They included Yogmaya’s daughter and her faithful brother and sister; they included her disciple Prem Narain and whole families of men and women and their children.

We know exactly what happened from a lad who arrived with his mother but fled in fear. He hid in a tree, it is said, to witness the event and later recounted to others what he had seen. It is rumored that another person was present but left after all the others had jumped. He took with him the list of signatures of women and men who sacrificed themselves with Yogmaya.

In Asian terms Yogmaya is credited with having prevailed over the ruler. He should not have allowed her to die. According to Hindu tradition therefore he bears responsibility for her death. So she succeeded in humiliating him, demonstrating by her death that he was incapable of offering a compromise. After Yogmaya, Mahatma Gandhi used the threat of suicide as a political leaver to achieve his goals. His confrontations are legendary. The self-immolations of Buddhist monks in Viet Nam will also be recalled. Are not the actions of Yogmaya and her followers of the same order? Moreover, is her act not a measure of the magnitude of her leadership? The speed with which the military moved into the area is proof itself of the seriousness with which the government viewed Yogmaya.

Why then is this heroine so little known?

Nobody disputes the suicides. And some of the survivors published what poems they could collect. This is an important document, a modest but real record of this piece of Nepal history.

After the rebel’s martyrdom, her people lived in fear if not terror. Majhwa was abandoned. The survivors must have been traumatized by the loss of their leader. They dispersed and spoke of the past only with great caution. They dared not utter the beloved hazurbani. Most copies of the small book of poems published in Kalimpong (Mani Press) disappeared from circulation. A few were kept in secret. (Only in 1985, after my third visit to the area, was I shown one of these thin yellowing volumes.) Nowadays, as you see, a few people who know the poems do sing the hazurbani.

Locally the story is well known. No one denies it; yet it is never discussed in public. If asked, people may offer some information about the movement. They are not keen to elaborate however.

Apart from what is in this booklet, the events were not recorded. Memory of the movement and the character of Yogmaya have become fragmented. Nothing affirms the events of or assigns them value today. “Old widows; they burn themselves”, some will tell you. “Communists”, say others. “Decadent women, a prostitution ring; immoral”, were the phrases used by people in response to my first inquiries about Majhwabesi. The people invoking these images are government personnel and local bystanders who speak of Yogmaya only with distain, or they try to avoid the subject altogether.

Contrasting with these attitudes are the reports of the devotees who cherish their leader’s memory.

While we can see that Yogmaya was far from forgotten, I think the evidence illustrates that this movement is recalled as if it were insignificant. It never entered Nepali historical consciousness. The effect is the loss to the nation of the contribution and the momentum offered by such a powerful force, by such a leader. Yogmaya was a troublesome widow, not a hero to many bystanders. Her utterances they interpreted as simply religious chants, not a political philosophy, her followers as merely “old women”, not activists for justice.

What are the cumulative effects of this memory gap? First, leadership remains something not associated with Nepali women, nor with the uneducated. Another more important outcome is that contemporary dissidents and idealists and nationalists, if they remain ignorant of Yogmaya. Are denied her as a resource in their contemporary ongoing struggles for justice. They may not know what they once achieved and therefore what they are capable of.

It is said that if a person does know that they have achieved something in the past, they can never enjoy self-respect.

Recent political events in Nepal call for further reflection and self-evaluation. With the unprecedented uprising across Nepal in 1990, I have new questions about Yogmaya’s place in history. Perhaps she merged into historical consciousness on that occasion. I am curious to know, for example, how dissent took expression in this in this part of East Nepal in the tumultuous months of February and March, 1990. As dissent spread at this time, it rose in the distant mountains of Nepal as well in its cities. Did it take hold in villages along the Arun River Valley more easily because it fused with the historical rebellion of the 1930s?

There is hardly any doubt that the virulent hazurbani can apply to a corrupt panchayat system and rule by the current monarch as much as they did to Rana misrule two generations earlier. So, were the hazurbani revived during the 1990 rebellion and did they help galvanize people in this latest struggle? It is possible. And if this happened, we are justified in feeling even more certain about Yogmaya’s leading place in her nation’s history.

I owe much to Janak Lal Sharma of the Department of Antiquities, Kathmandu who has many more materials to share about the Josmani sect. I am also grateful to Madev Shamshere Rana, to Dambar Bahadur Basnet who recalled many personal memories of Yogmaya for me, to Lochan Nodhi Tiwari and Uttam Pant, and to Harka Bahadur Gurung and Parizat– both of whom especially encouraged me to pursue this worthy history when traces where so faint. Most of all I have the women of Manakamana temple to thank.

References

Aziz, B.N. 1979. Indian philosopher as Tibetan folk hero; Legend of Langkor: a new source material on Phadampa Sangye. Central Asiatic Journal 23, 19-37.

Aziz, B.N.1982. A pilgrimage to Amarnath. Kailash 9, 121-38

Aziz, B.N.1983 Sacred encounter at Amarnath Cave. Natural History 92, 45-51.

Aziz, B.N.1987 Personal dimensions of the sacred journey. Journal of religious studies 23, 247-61.

Aziz, B.N. Sharma, J.L. n.d. Josmani santa parampara ra sahitya (Nepali text). Kathmandu.