by Barbara Nimri Aziz December 2015

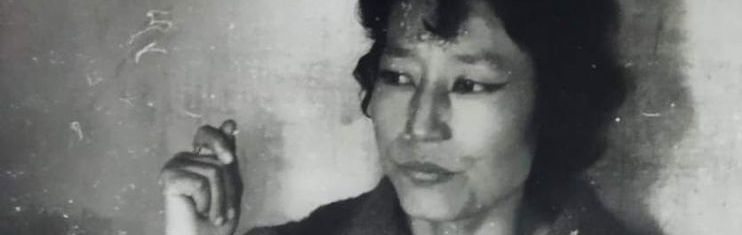

My first encounter with Parijat Lama, the remarkable activist, poet, and humanist, was more momentous for me than I expected.

Nepali friends, knowing the poet and I had widely different backgrounds, often ask me how I met Parijat. My reply: “Yogmaya, the ascetic Bhojpuri activist who’d challenged the Rana ruler, introduced us.” This was true, even though Parijat and my friendship began in 1981, long after the height of Yogmaya’s campaign and forty-one years after her passing. So I have to start with a brief account of how I first met Yogmaya.

From 1969, as a foreign anthropologist working in Nepal I spent little time in the then-uncrowded capital. Like others in my profession I was there to study what we called ‘minorities’. I started in Solu among Tibetans newly settled there. Research work was rigorous and demanded months of isolation. Compared to today, facilities in the hills, even in Solu, were severely limited.

In 1980, I set aside my work among Tibetans after becoming aware of the profusion of tirtha throughout Nepal (as well as India.). Hearing about a revered tirtha at the juncture of the Arun and Barun rivers, I set out for there walking east from Solu.

Reaching the bank of the Arun River below Dingla after our hard trek, we intended to rest for only a day and found respite at a quiet riverside ashram at Manakamana ghat.

By morning I abandoned my plan to continue north to the Barun. Because that night I was struck with a new mission after hearing a woman chanting what turned out to be utterances (still secret at the time) by Yogmaya more than fifty years earlier. Those poems’ inexplicable force compelled me to pursue their meaning. They would define an entirely new and unforeseen assignment for me; they led me to Parijat, to a political awareness and my own personal political mission through journalism.

Raja sits in his palace/and does not care to see/if the poor have justice/not even justice by chance (by Yogmaya Neupane, 1930s, Bhojpur)

Most of its then elderly inhabitants of that riverside retreat had been devotees of Yogmaya more than 50 years earlier; they had heard the bani directly from her. The vigor of their recitations overwhelmed me and I pressed these aging bhaktini about their origin. “These are hazurbani, verses by Shakti Yogmaya, our departed Guru.” Many of the bani were indisputably political. The survivors of that campaign explained how their guru challenged corruption and caste discrimination, how she called on the Rana ruler to halt abuse and to grant equality. I realized hazurbani were Yogmaya’s means of fighting injustice.

Finding few details of Yogmaya in books or from scholars in the capital I made another visit to Manakamana. I was met with an even more critical finding then, when Mata Damodara, head of the retreat, gifted me a small printed collection: Sarvartha Yogbani the poet’s work. Its publication in 1940 in Kalimpong gave Yogmaya’s life a new dimension. This was not a myth or a local religious episode.

Departing from Manakamana with Mata’s gift, I asked if there was another woman poet in Nepal known for her political missives. “Parijat”, replied the young man who’d made the initial translations for me. “She’s in Kathmandu; I never met her, but boys move through the hills reciting her verses.” She would surely know more about the author of the Sarvartha Yogbani, I thought.

Arriving in Kathmandu with the thin booklet in hand and led by a nephew of Parijat who’d overheard my inquiries in the small hotel where he worked, I found myself at the gateway to this notorious yet much loved woman’s home. Parijat agreed to receive me. Generous, since she did not know the reason for my visit. (She took a dim view of anthropology as well.)

“So, you’re an anthropologist,” she began. “Anthropology is a product of your imperial culture; it has no benefit for us. It’s used by foreign powers to dominate us.”

I couldn’t disagree with Parijat. ‘Anthropology Is the Child of Imperialism’ was an essay I’d read in college. Although aware that I was a product of that ‘imperialist machine’, I did not reject this role, arguing my research contributed to human understanding. Those days, probably today too, most foreign scholars and other visitors to Nepal were unconcerned with domestic politics. (Then it was the archaic monarchy; today it is modern multi-party tussles and scandals.) Perhaps our disinterest parallels how Nepalis in USA devote their attention to personal advancement and leave American politics to longer-settled citizens.

Parijat’s room was a crossroads. One youngster brought me a copy of Blue Mimosa, Parijat’s only translated work at that time. Another came in with tea; a third stood nearby, enchanted by us speaking in English. A visitor arrived and sat quietly listening. No formalities. The devotion of those moving around her was deep and authentic. She stopped each child and visitor to introduce them, telling me their village and family circumstances, and why they here with her. Through simple personal stories of everyone I met there, I would learn about her ideology and her mission.

After we shared a cigarette, I told her where I’d been in East Nepal. I removed the harmless-looking book from my bag and offered it to her. She examined The Sarvartha Yogbani in deep concentration. Then she looked at me, her eyes wide in amazement. “Where did you find this? How, when, from whom?” She flooded me with questions about Yogmaya as she continued studying more of the entries. She recognized both Yogmaya’s literary genius and her political sagacity immediately. The bani’s authenticity pierced her heart.

Fat bellies burst/ and those bribes ooze out/ to poison you/So savour your riches while you can. (Yogmaya Neupane, 1930s, Bhojpur)

That the creator of these remarkable verses was a woman was important to Parijat too. She urged me to return to that ashram and learn more from Mata and the others. On my upcoming visit there she sent a student with me, the daughter of her dearest friend. Meanwhile she eagerly agreed to help translate some verses and she invited two devoted followers to assist her while she made further inquiries about Yogmaya Neupane’s history.

Why I did not urge Parijat accompany me to Manakamana herself, I don’t know. I very much regret this. Regular air service was available into Tumlingtar in 1981, and helpers would assist us reaching where Yogmaya’s devotees lived, barely an hour’s walk upriver. Sadly, neither of us considered this expedition.

Despite her difficulties, due to her arthritis, gripping a pen, she continued to write and move beyond her house. Parijat often travelled outside the capital by motorbike or bus. She was not like most Kathmandu residents who disliked leaving the valley, especially to hilly regions without roads and electricity. I wonder: if Parijat had gone to Manakamana ashram how much more we would have learned about Yogmaya’s history. I imagine she would have been inspired to write a great deal about the woman she called ‘my ancestor’.

For the next eight years, I travelled to Nepal often, for short periods to revisit Manakamana (where I was learning more about Yogmaya and also the history of Durga Devi, yet another Bhojpuri rebel), and to meet Parijat.

We didn’t always talk about our work. I frequently joined her, her sister and another woman to visit local momo shops and drink raxi or tomba; we entertained ourselves for hours in lighthearted banter. Even of her adversaries, she never expressed hatred. She mocked them with her cutting puns, ridiculed them and delighted in slanderous gossip.

When in the capital, instead of searching out professional colleagues, I headed to Meh Pin neighborhood, then on the edge of the city– direct to Parijat’s cottage. I became her student as much as her friend. I think this happened to most of the men and women who spent time with her.

I assumed she used her quiet morning hours to write. The rest of her day, she received visitors in her casual style, whatever their rank. She and her sister Sukanya Waiba lived their political convictions in daily intimate, informalities. That’s how it appeared to me as a novice and a foreigner. I was not present for their intellectual exchanges; but I heard no ideological invocations or pronouncements. Neither woman were ideologues. Although posters of their ideological heroes – Che Guevara and Karl Marx– looked out on us from the brick walls of Parijat’s room. No need to explain Socialism or Marxism when they lived them from morning to night.

Whenever I was at Meh Pin, 2, 3 or 4 visitors arrived daily – women, men, youths, children, students – wounded, weary, anxious and courteous. They came with news, in search of advice; they found comfort here.. Like the calm, assuring way Parijat impacted them – people in need and aspiring writers alike– she effected me.

So much so, that being near her I forgot the dangers of political gatherings and strategizing at that dangerous time in the country. I was not privy to conversations in Nepali of course, but I learned much from her interactions with the multiplicity of people around her. Her calmness and humanity and fearlessness infused me, as it likely did them. I forgot the dictator’s security detail posted beyond the courtyard to note whomever came and went. I forgot that I too might be suspect, and expelled. I forgot the risks everyone took upon entering this cottage; I forgot the military’s readiness to sweep into a home and arrest suspected critics of the ruler; I forgot that her own brother-in-law was a fugitive, an underground Marxist leader against whom an arrest warrant was issued by the regime – not even his family knew his whereabouts. I forgot that leaders of any of Nepal’s opposition parties were forced into exile; I forgot that not a word critical of the king and his government appeared in any paper. I forgot about those students tossed by police from balconies of their college residence, and the rumor of a murderous raid on a cell of anti-monarchy activists somewhere near Okhaldunga.

That corona of calm around Parijat testified this woman’s power, her sister’s too. Their influence was known to authorities—if not from informers, then from Parijat’s own writing. She was pitilessly yet calmly honest. She wrote and spoke equally freely about her personal life and her social and political ideals. Such candor was rare, from both men and women. Why she herself was not arrested, I could not comprehend. Perhaps it was her ill health. Perhaps authorities believed that any move against her would provoke widespread reactions that their police could not contain.

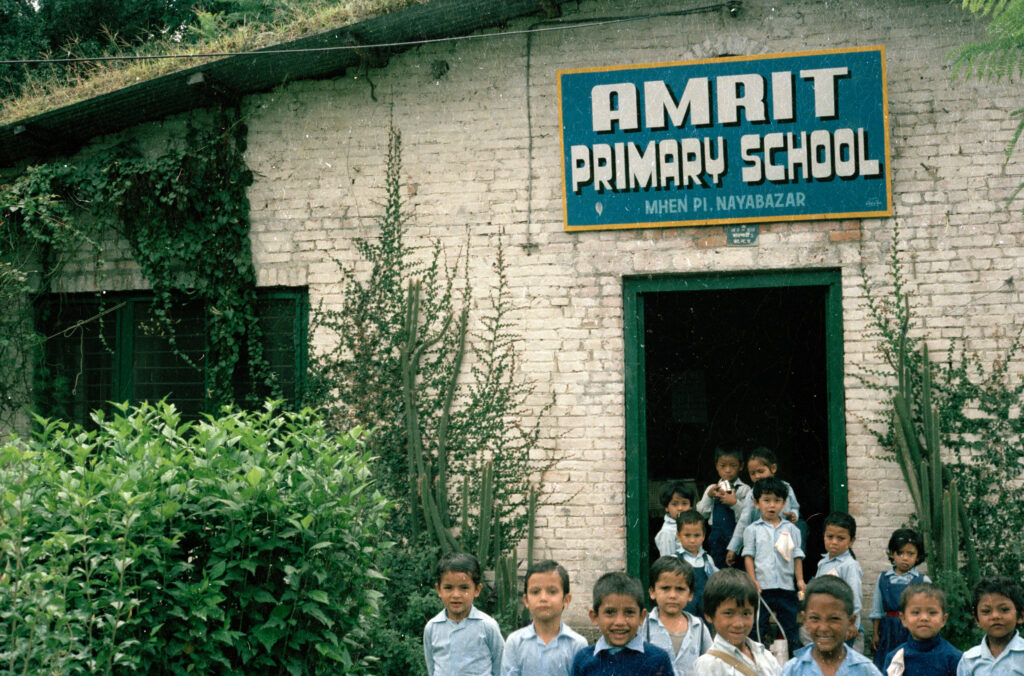

In any case, she used whatever narrow license the ruler permitted to write what she wished and to receive visitors. She found clothes for people needing help, fed anyone who arrived at her door hungry. Somehow she found jobs for those wanting work; she housed youngsters so they could attend the school that she and Sukanya had recently founded. She arranged a safe place for children of imprisoned women and men. She sheltered women fleeing drunken husbands and abusive mothers-in-law.

Parijat hardly needed to travel beyond Meh Pin to learn about conditions far and wide. People arrived from across the country reporting hazards, obstacles and exploitation as well as possibilities and progress. Her personality and openness, her readiness to receive anyone, her gentle voice: all fostered a feeling of protection. On her side, she acquired a true picture of conditions in Nepal, one few could match and assess.

How fortunate I was to witness her in action. Yet I was more than a witness. Being with Parijat and Sukanya I grasped in real terms what Yogmaya had written about and fought against decades earlier. If I was to comprehend Yogmaya’s biting metaphors and imagine the risks she took, I had to confront political realties still deeply entrenched in Nepal. I had to break the intellectual confines of anthropology and reject the patronizing, western lens through which I had viewed Nepal. I had to allow my personal admiration for that historical Bhojpur rebel into my writing.

I could not have done this without political tutelage, and this happened there in that Meh Pin cottage. I began to understand Yogmaya and the realities she had faced after I first lost my own fear of government censure and broke the strictures of anthropology. Seeing how Parijat managed, how she lived Marxism daily and fought injustice through blunt honesty and by sharing with others whatever she had, helped my resolve. If conditions under the monarchy were so restricted in the 1980s, how many more obstacles did Yogmaya face opposing the Rana regime in the 1930s?

It took a long time to develop a new medium in which to plant my research. Too long for my Meh Pin teacher to see the result– essays on Yogmaya and Heir to a Silent Song: Rebel Women of Nepal . Eventually others, notably Neelam Niharika, Dipesh Neupane and Matrika Timsina, and picked up the traces and began to explore Yogmaya’s history more fully. Parijat would be very gratified.

END