July 5/21 by BNimri Aziz.

Being a widow presents difficulties for many young women in South Asia. This includes Nepal where Durga Devi Karki, the woman I want to tell you about, achieved remarkable legal victories as a widow. She did this early in the last century, and essentially on her own.

Widowhood in youth is especially onerous. It’s a harsh life sentence for girls of high caste Hindu families who find themselves widows even before they cohabit with their betrothed. Forbidden to remarry, they remain childless and dependent on others’ forbearance. Although that custom is now illegal, widows, young or old and without sons, often experience undue hardship. Any woman seeking a just alternative for herself would have to be skillful and resolute, also prepared for a protracted fight. Enter Durga Devi.

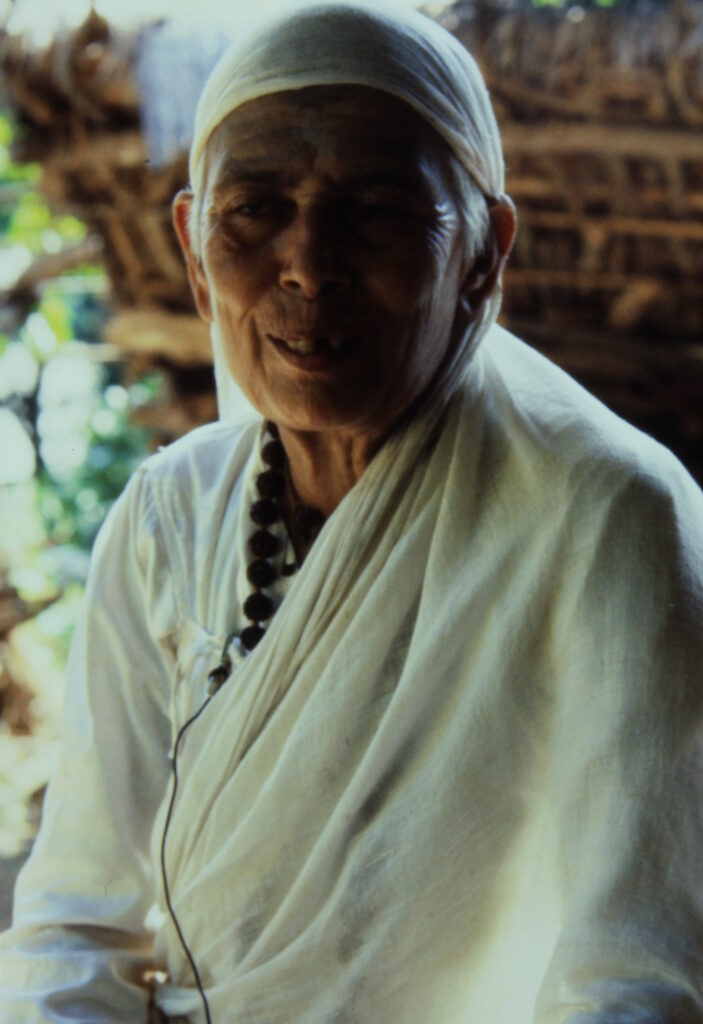

Born in 1918 in a remote Himalayan village, Durga Devi’s unyielding pursuit of justice evolved into a combative and colorful career. To the people whom she aided, she was “Vijayi (victorious) Devi”; many more would remember her as “samasya”: troublesome. Details of her youth and the campaigns that won her these monikers you can find in my book Yogmaya & Durga Devi. Briefly, here are some highlights from Durga’s life documented there.

Not unlike other lifelong activists, Durga Devi was motivated by injustices she encountered early on. When her betrothed died, Hindu custom doomed her to a lifetime of widowhood; this would also deny her full partnership in her husband’s household.

We don’t know why Durga Devi didn’t challenge the ban on remarriage which also required her to move to her in-laws’ residence. But she drew a line:– she would not consent to anyone usurping her property rights there and she vowed never to be consigned to the margins of that household.

Asserting such a radical position was risky and drew strong opposition from Durga’s brothers-in-law. Prepared for the rebuff, Durga resolved to take her claim to court. Which she did, and astonished everyone by winning her entitlement. The humiliated brothers-in-law then connived to betroth Durga, hoping to finally rid themselves of this troublemaker. Again, she fought back. Again, she prevailed.

Afterwards, emboldened and living independently, Durga Devi turned her attention to everyday transgressions in her neighborhood. She reported on merchants who cheated shoppers while police looked the other way; she called out slothful town clerks who derided humble farmers seeking permits and advice.

She spoke in defense of women beaten by drunken husbands, against men unilaterally bringing a second wife into their house. Learning of the rape of a deaf and homeless girl, Durga singlehandedly came to this child’s rescue, scouring the locality until she identified the villain. She later arranged support for the violated girl and her baby.

Conditions Durga spoke against should motivate anyone to act. She was alone in challenging injustice and seeking redress.

By any reckoning, notwithstanding what she endured personally, this woman’s victories should be impossible. A widow is expected to assent to her in-laws’ will, turning over management of her land, accepting whatever crumbs the family grants her. She should be neither seen nor heard in public.

Let’s not forget general conditions in Nepal a hundred years ago. Durga Devi and other children had no access to school. Even following Nepal’s introduction of universal education (1970, three years before Durga’s death), initially few girls were found in primary classes. Democratic institutions would not exist until after 1990. Nepal was a feudal society ruled by an absolute monarchy; free association was banned, political dissent crushed. Apart from district courts, no agencies existed to address citizen needs. Police worked hand-in-hand with corrupt officials and landlords. Patriarchy, sanctioned by Hindu religious authority, was pervasive.

Nepal’s abused and exploited women, like others across the world with no means of redress, frequently run away. Some may enter a religious retreat. More often they take own life.

If Durga Devi could overcome obstacles presented by such severe conditions, she is unarguably worthy of public recognition, a heroine similar to ‘forgotten’ women worldwide who have been rescued from obscurity by activists and civil rights advocates, their accomplishments often belatedly recognized. When her career is fully uncovered, Durga Devi will stand in the company of international figures, pioneers like physicist Mileva Maric (first wife of Einstein), and American mathematician Dorothy Vaughan and her colleagues. When the spotlight eventually turns on Durga Devi, it will reveal a proud Nepalis legacy, showing what was possible for women to accomplish even a century ago.

Although Durga Devi seems to have been a lone campaigner, at critical periods in her growth, she had help:–first from her father, then from Sasu (her mother-in-law).

Durga’s father, Sher Bahadur Karki, turned to young Durga Devi as a pseudo-heir when his only son died. He could not give his daughter land, but he could teach her to read and write, and next to employ her in his legal pursuits. Father and child were reputedly an awesome team, traveling to and from Bhojpur district court enjoying one victory after another.

Later, at her marriage residence, Durga Devi somehow won the loyalty and affection of her Sasu. It was Sasu who passed her daughter-in-law the land deeds so she could pursue her legal claim. When Sasu’s sons schemed to marry off Durga, Sasu’s warning enabled Durga to escape. The two women became such allies that, in a stark break with custom, the older woman on her death bed ordered that Durga, not her sons, conduct her funerary rite. Years later, at that same riverside site, when it was Durga’s time, she called the family and read them her written testament concerning the disposition of her wealth.

Despite the vivid images people recall from her exploits, Durga Devi fell into obscurity for some decades. It is not an uncommon end for formidable individuals whose words and actions break norms and threaten the establishment. Today, Durga’s name no longer elicits embarrassed silence or scorn.

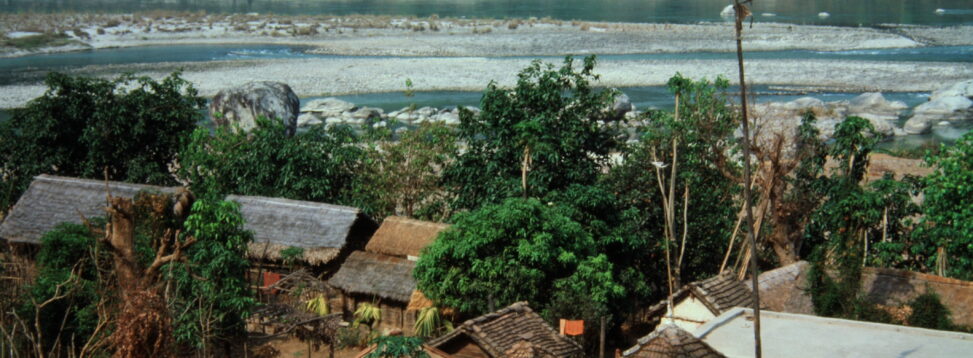

It was by sheer chance that she managed to come to my attention after an innocent question posed to mostly elderly widows residing in a remote heritage on the shore of the awesome Arun River over gigantic boulders, flanked by steep terraced rice fields.

“Who owns this land where you live.”

“Durga Devi bought this for us. She planted the fruits trees too. She built the shrine for Manakamana; and she opened the trail down here.”