Book review by Barbara Nimri Aziz. July 2016

A Muslim youth commits a terrible violent crime and then takes his own life. His suburban family, immigrants in the US for more than two decades is advised to relocate; his parents are divided over how to handle the crisis; his teenage siblings, shunned and mocked by classmates, retreat into fantasy; the community in which they were once so nicely integrated spurns them.

The scenario could be any national news story. Whatever the perpetrator’s motive or mental state, his crime is a ‘Muslim’ one– an uncivil act; everything associated with him becomes tainted. The religion itself is blighted and criminalized. The violence is seen as further evidence that Islam bears responsibility.

Our media’s preoccupation with and prejudgment of this category of crime is so intense that Muslims find themselves floundering in its wake. With regular frequency, Muslim writers pen commentaries explaining our angst, and cohorts of Muslim spokespeople appear on TV to refute generalizations about Islam and to assure others of the peace-loving nature of our religion and our community.

We know the scenario too well. Yet those eloquent efforts seem naïve, ineffective and superficial. At the same time we find precious few attempts by our Muslim creative community to explore the human repercussions of these events at a deeper level:–through novels, film and drama.

I can think of just three writers, Hanif Kureishi, Wajahat Ali and Laila Halaby who’ve addressed Muslim family experience in these turbulent decades in the West where our social lives are thrown into turmoil, where we are psychologically traumatized, and where our own spiritual values are undermined. (“My Son the Fanatic”, a 1994 story by London-based Kureishi was made into an excellent film; Ali’s 2005 play “Domestic Crusaders” was later published as a book; Halaby’s novel “Once in a Promised Land” appeared in 2007. I suppose we could include “My Name Is Khan” a 2010 Indian-produced film set largely in the USA.)

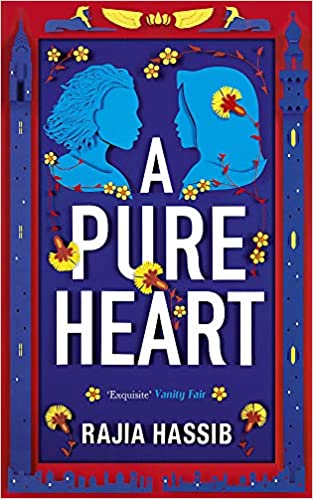

We now have a novel that tackles this contemporary theme in a fresh and effective approach. Rajia Hassib’s “In the Language of Miracles” (Viking, 2015) explores how one American Muslim family is impacted by violence. I don’t know if Hassib intended her fictional piece to be a domestic prism through which to view the American Muslims’ experience of “terror” in our midst. Because there’s nothing explicit here about what’s commonly labeled “Islamic terror”. For me however, her story is essentially a metaphor of our recurring nightmare– “Islamic violence” directed at Western targets.

The plot of “In the Language of Miracles” is an astute tactic to remove the crime from its normally fraught political context to explore what transpires when a simple youth, motivated by jealousy, family tensions and personal stress, carries out an ordinary (American) killing. What happens to his family and his community?”

This cleverly crafted story opens with a veiled reference to a past family tragedy when Cynthia, a (white) neighbor invites the Al-Menshawy (Muslim) family to a forthcoming event; it’s the first anniversary memorial of her daughter Nathalie’s death. The invitation precipitates divisions among family members: Samir, the father and a successful doctor, his wife Nagla suffering from unspecified ailments, their son Khaled, their daughter Fatima, and Nagla’s mother Ehsan visiting from overseas. Each reacts differently to the neighbor’s invitation and we are pulled into the evolving drama over the few days between that awkward announcement and the ceremony itself. We soon learn that the al-Menshawys not only also lost a child, Hosaam, by suicide; it was their son who killed Nathalie, his longtime childhood friend.

We hardly have time to mourn Hosaam or to learn his motives since author Hassib’s story focuses around Nathalie’s approaching memorial which is to be a community affair with speeches and a tree planting. Flyers are posted on social media and across the town, stirring up the community’s grief and anger; not unexpectedly much emotion is directed at the killer’s family.

What should they do? Samir insists they attend the memorial where he intends to make a statement. Nagla rejects this; she’s unfocused and indolent, a condition likely precipitated by the death of Hosaam. Her surviving son Khaled is withdrawn while Fatima tries to ride above the fray. (She has recently befriended another Muslim girl and is perhaps becoming more devout.) Khaled, rejected by all but one school friend, retreats into social media and seeks out a young woman in New York City. With this stranger he’s able to share his distress and revisit events leading to Hosaam’s action. He returns to his troubled home in New Jersey in time for the memorial but too late to rescue his father from his blundering performance there.

The story is presented through Khaled’s eyes, from his grandmother’s pseudo-Islamic incantations and dream interpretations during a childhood illness to his alienation from his brother, the son for whom Samir had high expectations. (In the final chapter we find Khaled and his sister residing in the US while their father, humiliated after his misstep at the memorial, has returned to Egypt with Nagla and their grandmother.)

To build the character of Samir whose psychology Hassib seems most interested in exploring, she takes us back to his arrival in New York as a medical graduate from Egypt to begin his residency. While achieving his ambitions of establishing his own clinic and enjoying social acceptance among Americans, Samir has eschewed his Egyptian culture and his religion. Yet he misreads the very culture he feels so proud to be part of; his children are unanchored and his wife is ill. Worst, he completely disregards his own son’s death anniversary.

Tellingly, the least acculturated family member, grandmother Ehsan, offers her folk remedies, common sense, and some invocations of Islamic texts that she barely understands to address the pain of her traumatized family. She alone seems to possess the cultural integrity to properly recognize the death anniversary of their child Hosaam. In familiar simple Islamic tradition she prepares special pastries and goes to the cemetery to commute with his spirit (and to scrub offensive graffiti off his gravestone) where she also consoles a grieving stranger at a nearby grave.