Published in Ceramics Monthly, March 1993. By Barbara Nimri Aziz.

Tibet’s otherwise bleak, brown land scape is sometimes broken by rust-col- ored hillocks. Located just beyond the mud brick walls of squat villages, these mounds are actually kiln sites, where accumulated ash and shards flash red in the sun.

Outside Tibet, I had seen only an occasional example of Tibetan ceram ics. The Staatl Museum der Volker- kunde (Museum of Ethnology) in Munich, Germany, has some fine samples obtained by expeditions early this century. And at a wealthy monastery in Nepal, one may see a teapot and brazier, carried there over the Himalayas in the 1950s when Tibetans fled from Chinese occupation. But that’s about all. In collections of Tibetan art around the world, pottery is generally absent.

Expatriated Tibetans continue to use traditional bowls and jars, but theirs are made from wood or metal. The production of Tibetan-style ceramic ware has not been taken up elsewhere.

The only place we can find such pots being made is within Tibet itself Pottery, unlike many Tibetan arts, did not suffer from the onslaught of the Cultural Revolution when the Red Guards leveled most of Tibet’s religious centers and forced so many artisans out of work. The communists considered pottery a utilitarian “worker’s art.” They therefore encouraged it, whereas the “re ligious arts” were suppressed. This is why potters in Tibet today are relatively numerous and active.

Even the introduction of hot water thermoses and plastic buckets has not seriously undermined the demand for pottery. For example, incense burners, soup pots, teapots and beer crocks are common in farmhouses and villages. There may even have been a resurgence of appreciation for those clay vessels as the people discovered that the new metal or plastic products were not as durable or as well suited to their needs.

At the open bazaar in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, the popularity of ceramic ware is abundantly evident. Near the butter market in the old quarter of the city, pottery is sold in a large courtyard. Broad, high vessels for distilling barley beer; elegant, small- necked teapots; and large fermenting crocks are displayed alongside a variety of flower pots.

Some Lhasa residents are among the shoppers, but most of this stock is bought up by farmers who come to the city to buy supplies. The pots are carried off, and regularly, as if on order, another three loads of pots arrive to fill the yard again.

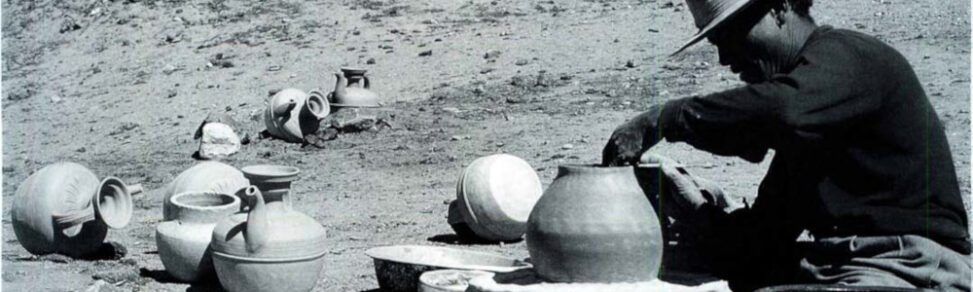

New stock, packed in straw, is brought to Lhasa on mule-drawn wag ons every week. I learned from the sellers and the muleteers that the pottery’s origin is Pemba, a valley to the north east of the city.

By wagon, the ride from Lhasa back to Pemba takes almost a day and a full night, so I turned down the offer of a free ride, opting to go there by bus instead. In under two hours, I was in the long, narrow valley with its villages tucked against the bare mountain walls rising from either side.

After walking into the village of Gyatso-tso, I asked for directions to Lobsang’s house. This well-known pot ter, I had been told at the Lhasa market, was sure to be at work. It was mid morning and, indeed, I found him seated in a sunny courtyard.

Potting is considered by some to be “polluted” work; artisans who work with earth, metal or animal skin are viewed as “unclean.”However much people treasure craft products, they feel themselves somehow superior to the makers.

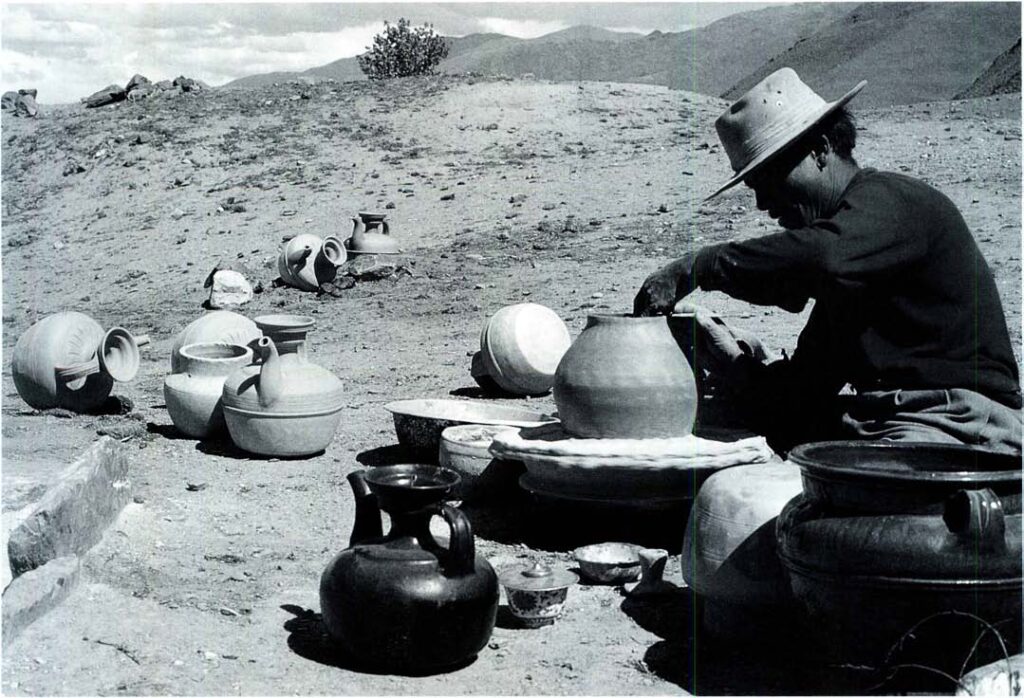

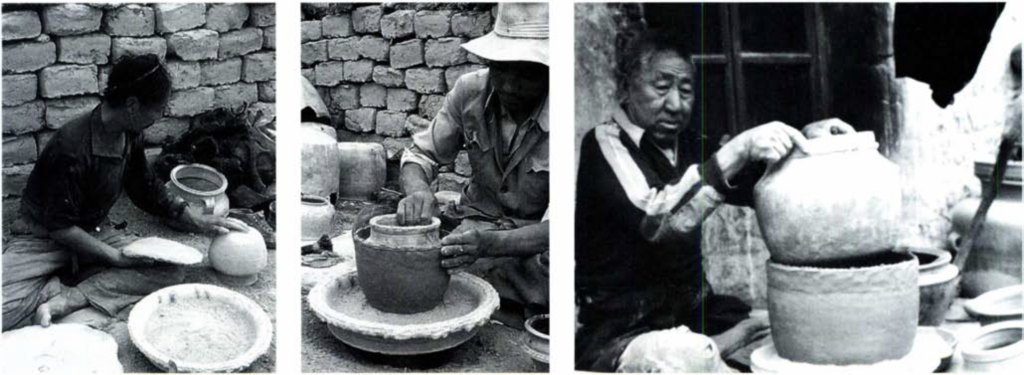

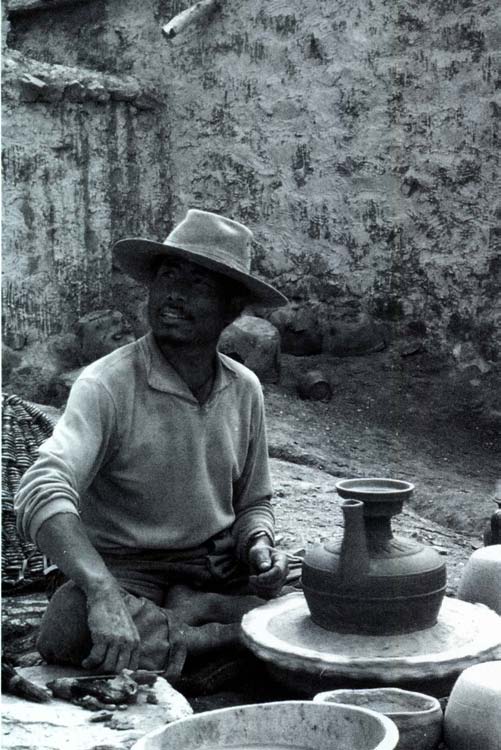

He sat cross-legged on a mat in front of a wheel, which he turned slowly with his toe. According to German ethnographer Veronika Ronge, a recognized authority on Tibetan pottery, the wheel consists of a fired clay head set on an axle fixed into a wooden support that, in turn, is embedded in the ground.

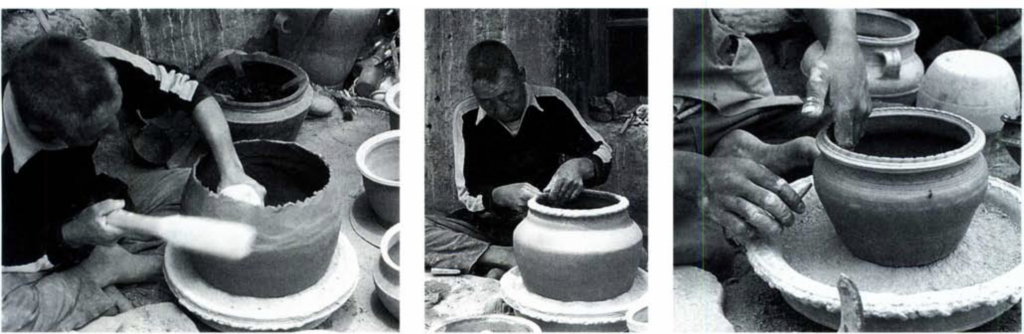

With his hands, Lobsang flattened a 2-pound ball of clay and placed it on the bottom of an overturned pot rest ing in an ash-filled basin on the wheel. He then pressed the clay around the form, working it down around the sides, occasionally powdering his hands with ash from a nearby bowl. In a small pot filled with water were two knifelike tools and a hog’s-hair brush used to moisten the clay. Also within his reach were a paddle and a kind of anvil with a wide flat head. When Lobsang paused, he would drink from a wooden cup nearby that Phuti, his wife, kept filled with tea.

In the shade of the porch, his 18-year-old son was weaving spun goat hair into a strip of mat ting, now about 6 feet long. This he would stitch together with five similar lengths to make a mat. Yak and goat hair are used by Tibetans for a variety of items— ropes, tents, saddlebags, mats—all are spun and woven by men. In contrast, all woolen goods and the wool itself are handled only by women.

A division of labor by gender is also strictly followed in the production of pottery, so neither Phuti nor other women may make pots. They can, however, assist their husbands in the glazing and firing. They often grindstones for glazes, help make the kiln furniture, stack greenware and fuel, and remove the fired pots. Apparently, the women also prepare bread dough before each firing so that, after the pots are unloaded, they can use the still-hot embers to bake. Good fuel conservation!

Pottery-making itself is further restricted to a certain class. In the past, and to some extent today as well, children of potters tended to marry others within their occupational group. As elsewhere in Asia, potting is considered by some to be “polluted” work; artisans who work with earth, metal or animal skin are viewed as “unclean.” However much people treasure craft products, they feel themselves somehow superior to the makers.

Lobsang, after he had more or less covered the sides of the pot used as a mold, smoothed the fresh clay with his hands. Turning his work over, he pulled out the mold and put it aside. Next, as his toe slowly turned the wheel, he began to paddle the side of the new pot very gently, forming the shoulder and the collar of the pot. Lobsang told me this was the most delicate part of making a pot. All his years of experience are focused here, he said

His son also makes pots, but is not skilled yet. Lobsang is not sure if the boy will decide to carry on the tradi tion, since most young, educated Ti betans want to do other kinds of work. Yet, he says quite confidently that his son could not find better-paying work than this.

The edge of the pots mouth was rough and thin. To make the lip, Lobsang attached a coil of malleable clay, then another, and finally moist ened the rim and fluted the edge. The pot completed, he lifted it off the wheel and rested it in a sunny corner of the yard, where the afternoon wind could not reach it.

Beer crocks, like that one, flowerpots and soup pots generally remain un glazed, but are brushed with slip before firing. Some Tibetan pots are also un decorated; however, braziers, flowerpots and beer pitchers often have simple de signs incised on their surfaces with a wooden stylus. The most common motifs are repeated patterns of lotus leaves, branches, waves and the symbol for long life.

Glazing is a simple procedure that involves coating the surface with one of three colors: dark green, earth red or brown. Phuti told me that the rocks used for glazing are expensive and difficult to obtain nowadays, so they make only unglazed ware.

Center: The clay-covered mold pot is then righted and set in an ash-filled basin on the wheel.

Right: After the mold pot has been loosened and lifted out, Lobsang will shape the wall of the new pot with a paddle and anvil.

Center: On some pots, the lip is fluted by pinching with fingers and thumb.

Right: Flowerpots (such as this), braziers and beer pitchers are often decorated by incising

simple patterns with a wooden stylus.

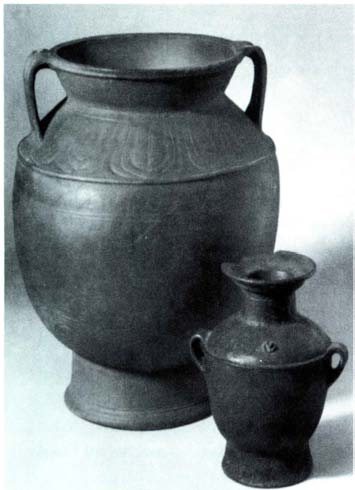

Tibetan teapots, however, are always glazed, and other potters go to consid erable lengths to obtain materials. Veronika Ronge has reported that they get borax from lakes on the high pla teaus and clay powder from central Ti bet; the minerals needed for green and blue glazes are particularly rare, so most pots today are glazed in browns and reds achieved with yellow ocher stone. “The composition of glazes,” she says, “is still not exactly known to outsiders, but I observed a potter mixing three parts lead, three parts borax and three parts powder with water.”

To see a teapot made, I traveled fur ther east to the village of Metakonga. The distinctive shape of the Tibetan teapot makes it the most elegant in the potters repertoire. A bulbous bottom narrows to a small neck, which widens again in a series of steps. The bowl is made first, following the same process for the beer crock and flowerpots I had seen in Pemba Valley.

The neck and mouth, like the spout and handle, are made separately. A nar row cylinder of moist clay is added to the mouth of this bowl base to form a neck. While the wheel is quickly spun, the potter uses a sharp, wooden tool to define the elaborate neck and lip. Some add relief designs—a dragon or bird head or flora—to the handle and base of the spout.

All around Metakonga lie the red kiln mounds. Smoke seeping from the top of several indicated firings were un derway. In most Pemba villages, a kiln is fired every ten days or two weeks. But because Metakonga has a greater concentration of active potters, one is more likely to find a kiln in operation on any given day.

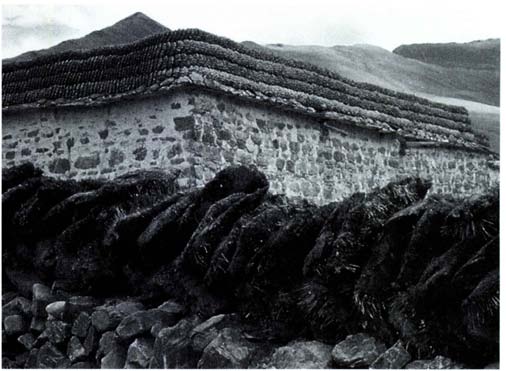

Fuel is the critical factor for ceramic work in this culture. Peat (called pang in Tibetan), a slow-burning, hot fuel composed of roots and other organic matter compacted over the decades, is considered ideal and essential for firing pots. The availability of good peat once determined where pottery villages were located.

Of course, local supplies of peat have long since been consumed. Nowadays, potters in places like Metakonga and Pemba Valley have to travel several hours by horse cart to collect the slabs of peat they need. They chop it out of the ground like sod. Collected only once or twice a year, the peat is stored in foot- long blocks, neatly set out along the edges of walls and housetops. It lays there for months, drying in the wind.

When ready to fire his sun-dried pots, the potter carries peat, along with straw and cow dung, to the kiln site. One layer of pots is arranged over the residue of shards and ash from previous firings. Peat and straw are placed be tween and over the pot layer, followed by another layer of greenware, then more peat and straw. Small pots may be loaded inside larger ones. Shards, posts and other pieces of fired clay are posi tioned between the pots to keep them separated. Finally the entire mound of ware and fuel is covered with a “lid” of peat bricks.

When the potter is satisfied that ev erything is in order, he pokes burning fuel (usually dried cow manure) through spaces between the peat. The peat and grass are kindled and, within three hours, the entire mass is ignited, burn ing slowly with immense heat but no visible flames. Several times during the night, he checks the kiln by poking a long, narrow tube into the mass to see if the fire is burning evenly.

This firing process takes an evening and a night; then the kiln, somewhat collapsed, takes a day to cool. The ideal pots are neither tarnished nor carbon ized by fire or smoke. Brushed clean, they are packed in straw for the wagon ride to market.

While ceramics in Tibet may not be what it was two generations earlier, it clearly remains a flourishing craft. Al most every village household has a clay incense burner with which, from the flat roof, a morning offering is made to the mountain deities. Every farm woman also makes barley beer, ideally keeping several crocks full of ferment ing grain. And for their three-day wed ding celebrations, each family needs a ceremonial beer pitcher.

Then there is the ubiquitous teapot. Many village houses and nomad tents will have two, and a monastery kitchen is equipped with several, along with the braziers to keep the pots warm.

Left: Brazier with glazed exterior; braziers are still popular room warmers in Tibetan homes.

Top right: Glazed teapot with attached silver lid Silver tea bowl and glazed teapot with silver and spout in unglazed brazier.

Silver tea bowl and glazed teapot with silver and spout in unglazed brazier. lid and spout.

In a few villages, I saw people using ceramic butter churns (called dza- dong in some areas). These oblong pots have small necks and mouths, and handles on opposite sides of the mouth. Two people sit on either side of the churn, which rests on a cloth base. Each grasping a handle, they rock it back and forth. Within an hour, clumps of butter will be floating in the milk. By then, the evening soup (a barley mixture with bits of sheeps cheese and a root called tomd) is ready.

Because few Tibetan houses (whether in towns or the countryside) have cen tral heating, ceramic braziers are still popular room warmers. These wide, open vessels are filled with a layer of ash topped with hot coals. A guest entering a Tibetan house is furnished with a brazier soon after taking a seat. Then a cup of tea is poured and the pot placed gently on this nearby brazier since the cup will be taken up many times before the visit is over.

The author, an anthropologist who has studied Himalayan and Tibetan cultures for more than 20 years, Barbara Nimri Aziz observed the production of ceramics during three research trips to Tibet.